GrantRant XI

January 31, 2013

Combative responses to prior review are an exceptionally stupid thing to write. Even if you are right on the merits.

Your grant has been sunk in one page you poor, poor fool.

The glass is half full

January 31, 2013

There is nothing like a round of study section to make you wish you were the Boss of ALL the Science.

There is just soooo much incredible science being proposed. From noob to grey beard the PIs are coming up with really interesting and highly significant proposals. We’d learn a lot from all of them.

Obviously, it is the stuff that interests me that should fund. That stuff those other reviewers liked we can do without!

Sometimes I just want to blast the good ones with the NGA gun and be done.

—

Notice of Grant Award

GrantRant X

January 30, 2013

Open the grant you are polishing up right now, pronto, and change your reference style to Author-Date from that godawful numbered citation style. Then go on a slash and burn mission to make the length requirement. Because lets face it we all know your excuses about reading “flow” are bogus and you are just shoe horning in more text.

That numbered citation stuff is maddening to reviewers.

happy editing,

Uncle DM, Your Grant Fairy.

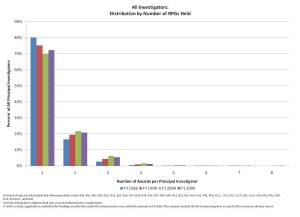

This figure was posted by Sally Rockey, head of the Office of extramural research on her blog Rock Talking. We have discussed these data in the past but given my recent Fixing the NIH series of posts, I thought it worth bringing up.This depicts the number of investigators funded by the NIH who hold a given number of Research Project Grants as Principal Investigator. This includes a range of R-mechs, U-mechs, DPs, Program Projects, etc. As Dr. Rockey noted:

This figure was posted by Sally Rockey, head of the Office of extramural research on her blog Rock Talking. We have discussed these data in the past but given my recent Fixing the NIH series of posts, I thought it worth bringing up.This depicts the number of investigators funded by the NIH who hold a given number of Research Project Grants as Principal Investigator. This includes a range of R-mechs, U-mechs, DPs, Program Projects, etc. As Dr. Rockey noted:

If you crunch the numbers, you will see that in each of the four years presented more than 90 percent of our investigators hold one or two research project grants.

And, if as I do, you spy a slight trend for increasing numbers of grants per investigator over time, I refer you to my analysis of the real purchasing power of the full modular ($250K in direct cost per year) R01. The short version is that the full-modular of FY 2011 had 69% of the purchasing power of the same award in FY 2001. A PI needs about $350K per year to have the same grant. Also note that the chances of suffering budget reductions upon funding and even on non-competing renewal, due to ongoing Continuing Resolution problems with Congress, has increased relative to the early noughties. So a little aggregate creep in the number of grants per PI should be expected.

The reason for Dr. Rockey presenting these data in the first place coincides with my reason for posting the graph today. Because one of the very popular “fixes” for the NIH incorporates some version of the assertion that there are some PIs who enjoy a huge amount of funding and that by preventing them from doing so, we’ll be able to give a lot more people a basic level of support. “Blood from a stone” is not precisely the right aphorism here but suffice it to say, there aren’t enough of these hugely funded labs to make a difference. Yes, of course, one R01 subtracted from Professor MoneyBags could go to Asst. Professor J.R. Mint and thereby make a HUGE difference in her life. But on the order of systematic fixes…..this does little.

This is the now famous cartoon by Dent which describes “types” of Principal Investigators. Obviously it is drawn from the perspective of trainees (no?) but it resonates with a timeless truthiness. To me anyway. And it is somewhat useful in our considerations for how to fix the NIH. We have to reduce the number of mouths at the trough, this is obvious. I’ve proposed that we need a prospective approach for the medium to long term future. I here renew my assertion that we need to get specific about which type of PI is to be put in the gunsights for reduction.

This is the now famous cartoon by Dent which describes “types” of Principal Investigators. Obviously it is drawn from the perspective of trainees (no?) but it resonates with a timeless truthiness. To me anyway. And it is somewhat useful in our considerations for how to fix the NIH. We have to reduce the number of mouths at the trough, this is obvious. I’ve proposed that we need a prospective approach for the medium to long term future. I here renew my assertion that we need to get specific about which type of PI is to be put in the gunsights for reduction.

Obviously, the answer is “That guy! over there….yeah, HIM. Not me, nuh-uh, I need to be preserved at all costs, dude!”

Sigh.

This is precisely why we need to have this conversation and precisely why the NIH needs to get more serious about making this hard call for themselves. Otherwise the culling will continue in an uncontrolled, random bolt-of-lightning fashion. Rockey called this “Darwinian” in (I think) a quote in a Science news bit AAAS bit. I don’t think that is quite the right term….laissez-faire maybe? At any rate. They are going to have to make the culling intentional if they have any interest whatsoever in 1) quality differences between funded investigators and 2) ensuring that the pool that remain after this great culling occurs is as high in quality* as possible.

One possible axis for pursuing this more-rational culling of the herd should involve thinking about types of operations. Small town grocer? Glamour Hound? Dreamer? Slave driver? Are any of these PI phenotypes associated with better value received for dollar spent by the NIH? Or is PI quality entirely uncorrelated with “type” of operation?

Raise your eyes back to the first graph. NIH has a lot of information on PI “type” based on the number of grants / dollars awarded. Some additional relevant information from University or Institute “type”. Does the size of the total NIH extramural portfolio (dollars, numbers of PIs, etc) at local institution influence success? They can, if they choose, do a bunch of retrospective peeking along a given PIs career track to see if a certain funding threshold at various points in the career are associated with success / failure. They need these data to evaluate Michael Eisen’s thresholds, btw.

I plead with you. As you engage in this discussion around and about…on blogs and in real life conversations….try to focus on the data we have. And the analyses that the NIH could conduct in the future. For these latter, demand them over at Rock Talk. Try to temper your knee-jerk “do it to that guy over there, my type of investigator is the BESTEVAH!!!” with some consideration of a larger picture. It is HARD. Believe me I know. Like I said elsewhere, I have no desire to be culled. None whatsoever. So obviously I’m looking very hard for arguments for why my type of scientist, my type of science, my type of job category and my type of institution are providing the best value. Given this, we should all double down on understanding and integrating data if it is available.

Recognizing that some 90 percent of PIs in the NIH system have only one or two RPGs is an example of what I mean.

Additional Reading on Fixing the NIH:

The NIH must dismantle the corrosive competitive culture of science

Shut off the PhD tap

We are going to fix the NIH

__

*yes there are many qualia that could be of interest here.

The NIH must dismantle the corrosive competitive culture of science

January 29, 2013

I like competition, don’t get me wrong. I engaged in inter-school competitive sports from freshman year of high school through my senior year of college. I played intramural sports from late high school through the end of graduate school. I’ve done competitive sports outside of school organizations from high school until…yesterday. Essentially uninterrupted.

Nowadays, I spend a solid plurality of my weekends schlepping one kid or another around to a competitive sporting event.

Just milk? sourceI love what competition does for us on many levels, of course. This should be obvious from the above. Of the many benefits, one thing competition does that is most useful is to make us strive to be better. It makes us practice to improve our play and our game. It makes us get fitter, more accomplished, more capable. It makes us attain performance levels we didn’t know we could reach.

This is true in science as well.

Science is indeed a competitive business, as most of my Readers know full well.

We positively reify the markers of success- getting a particular scientific discovery first. Accomplishing some demonstration or discovery with the greatest panache. Coming to a realization or theory that changes the way everyone else thinks about a topic. Creating a medical therapeutic approach…or the basis for such a thing. The accolades are both arbitrary (prizes, “respect”) and specific (grant funding, jobs of increasing worth, etc). At heart, scientists are trying to learn things about the function of the natural world and so there is an overlying competition to advance knowledge.

In all of this, the pot is sweetened by the competition. The scientist receives part of her respect not merely for accomplishing a certain task but for doing it before, or better than, the next scientist.

AP photo from here

This reality can be fantastic for science. As in sport, the competition makes us work harder, make us work to up our game and motivates our excellence. This speeds the advance of knowledge. One of my favorite formative anecdotes was the late 80s-mid 90s competition between several laboratories to comprehensively identify the role that various medial temporal lobe structures (e.g., the hippocampus) played in memory function. In this case the competition was made more acute (as it often is in science) by disagreement. One lab thought structure X really did Y and another insisted it did Z. Or Y’, perhaps. And every year the Society for Neuroscience annual meeting would have a hilarious slide session in which the labs would bash away at each other. Almost always…pointedly. Sometimes in semi-personal attacks. Then they would scurry back to their labs, publish a paper or three and come back next year ready for more battle with their latest results. Understanding was advanced.

This is where we depart from competitive sports.

The key feature in my anecdote is that the labs would publish. Most if not all of their results. And they would discuss their latest findings at meetings. With. their. competitors. Knowledge was built not just by the major players but by anyone else who cared to chip in as well. Because there was a superseding goal that went beyond the simple question of who crossed a line first or who scored the most points.

That goal was the provision of knowledge to everyone. Because scientific advance requires a collaboration amongst many. This is why we publish papers that include full methodological description. This is why we are expected to be honest about how we did a particular study. This is why we are expected to share the very intellectual property that was necessary for the experiments!

People seemed to understand this, and acted accordingly, during the medial temporal lobe memory warz.

The trouble comes when we start behaving a little too much like sports competition.

Before I get into it, another analogy. Take business. It used to be that competition was about money, yes, but also about providing a service or building a widget. Making something that people wanted and needed. The marker of success was not just driving your competitors out of business…but in being the best to provide rail service from New York to San Francisco. To supply an automobile that people could afford….and that worked. At some point, business became more about scoring the most points or crossing the tape first. The role of arbitrary performance indicators (unimaginable sums of money, unconnected to anything that could be viewed as necessary for the participants) in motivating behavior totally supplanted real indicators. And in many cases the product or service suffered tremendous harm. As did the consumer.

We have reached this point of transition in science. The marker of success is the mere fact of publication* of a paper in Journals of established, but arbitrary, rank. It is no longer about the actual finding or any sense of advancing science or knowledge. Papers are increasingly disconnected from each other and from anything that is of any reasonable importance to know.

So why should the NIH care? No, I don’t mean for the last point here. Yes, the relevance of work funded by the National Institutes of Health does concern me. However, the appropriate valuation across the scales of “basic” to “applied” research are not the topic of today.

The topic of today is the efficiency with which the science that the NIH pays for is advanced.

Sadly, we are in a time of great secrecy within science. Because being first** to some finding is rewarded above and beyond all other things, the very essence of the competition demands not letting anyone else know what you are doing until it is published. The typical manuscript in our most respected journals requires many person-years of work. And much of this work never sees the light of day for various reasons. It is negative. Merely supportive. A blind alley. Or perhaps just of insufficiently amazing interest.

More sordidly, much of this work never sees the light of day because it might help a competitor lab to beat us next time.

This is being done on the NIH dime. Right now, in labs all across the US. Many, many hours and $$$ of work being conducted that will never see the light of day (i.e., be published).

Admittedly there is a lot of work that nobody wants to see. I get this. I am no fan of Open Notebook Science. I want scientists to present their work to me somewhat triaged for interest. But we are well down the road from that level at present.

The “cost” to the NIH is not merely the invisibility of data and findings that they have already paid for. It is also in the future expenditures as another laboratory has to repeat the same experiments, generate the same blind alleys, waste the same time evaluating bad reagents or theories.

Sadly, some labs even lay a false trail by describing their Methods so incompletely that other labs get a wrong impression of what needs to be done.

This can burn years of a trainees time in a lab. No joke and no exaggeration.

And we haven’t even arrived at the discussion of fraud which is also driven by the arbitrary markers of competition.

Time for the NIH to get interested in the way that competition for arbitrary markers in science is wasting their precious taxpayer dollars. Long past time. I’m thinking of writing Sen Grassley’s committee myself! (kidding.)

Solutions? Well, we’re faced in part with a Justice Potter Stewart solution in that we can identify wasteful, GlamourPublication chasing laboratory operations when we see them. We can also take a stab at estimating how many person hours of work are surely being buried in the process but this will start to get a little…forensic. But if it were easy…..

I’m going to suggest going after Glamour idiocy at two places. Empower the Program Officers to demand a better ratio of work payed for to publications resulting, first. Second, the study section. Yep, beef up the analysis of “productivity” by creating a set of bullet point guidelines for how to asses. They have them for the other aspects of grant review, right? The Significance, Innovation, etc criteria? Well, no problem beefing up the assessment of Productivity.

Heck, this should be a formal criterion on all grant review, not just continuation proposals. It dovetails nicely with Michael Eisen’s proposals for lab-based or person-based funding, doesn’t it? How many people have you had working in your lab and how many figures have been published? What is your total lab support, including fellowships, TAships, etc for your trainees? Have you published as much of this work as you possibly can?

Or are you engaging in competition for arbitrary markers and are relegating much of the work to the dark corners of forgotten harddrives?

Additional Reading on Fixing the NIH:

Shut off the PhD tap

We are going to fix the NIH

__

*If you ever catch yourself saying “my Cell paper”, “the Jones lab’s Nature paper” or “her Science paper” in preference or addition to a short description of the topic of the paper….you are part of the problem. And you need to step back from the brink of GlamourDouchery before you fall in for good.

**Two labs could have the essentially same idea about solving a given problem, say the function of a gene. They could beaver away with 5-20 people contributing various science over the course of years. With many millions of dollars of NIH funds expended. If they happen to wrap up their “stories” a mere two months apart, this can be the difference between being accepted into Science or Nature or not. It may even be the case that the second one to be ready is a better demonstration on all features and yet the priority, the mere fact of submitting it for consideration first, rules the day. This is profoundly disturbed.

What is even more disturbed in the system is what happens next. Many aspects of the paper which has been beaten to the punch may not be published at all! That’s right. For the type of lab that is competing on the “get”, i.e., the mere fact of a Nature or Science acceptance, it is “back to work, minions!” time. Time to take the “story” beyond the current state of affairs and hope to win the priority battle for the next story which is big enough for Science or Nature to take it. At the very least replication is lost. More likely, there are a number of differences between the two studies, differences that maybe were of interest to other laboratories. Of interest for different reasons to the same laboratories. Or may later come into focus ten years later because of additional findings. Yet because of the competitive conundrum of science, many of those findings will be lost forever.

ETA: Forgot my disclaimer. I have, in many ways, tried to run to daylight in my scientific choices. This is in part due to what is an intrinsic orientation of mine, in part due to accidents of training history and in part due to explicit decision-making vis a vis the career on my part. I avoid competitive nonsense. I am not in the Glamour Chase. I am not entirely certain whether or not various steps to dismantle the bad effects of Glamour chasing, scooping, priority focused science would be good or bad for me, to be honest.

Shut off the PhD tap

January 28, 2013

We need to stop training so many PhD scientists.

It is overwhelmingly clear that much of the quotidian difficulty vis a vis grant funding is that we have too many mouths at the NIH grant trough. The career progression for PhDs in biomedicine has experienced a long and steady process of delay, impediment, uncertainty and disgruntlement, things have only gotten worse since this appeared in Science in 2002.

The panel’s co-chair, biologist Torsten Wiesel of Rockefeller University in New York City, is surprised to learn that this aging trend continues today: “You’d think with all the money that’s going into NIH, [young scientists] would be doing better.” His co-chair, biologist Shirley Tilghman, now president of Princeton University, says simply, “It’s appalling.” The data reviewed by the panel in 1994 looked “bad,” she says, “but compared to today, they actually look pretty good.” She adds: “The notion that our field right now has such a tiny percentage of people under the age of 35 initiating research … is very unhealthy and very worrisome.” …Experts differ on why older biomedical researchers are receiving a growing share of the pie these days and on what should be done about it. But they agree on the basic problem: The system is taking longer to launch young biologists.

We need to turn off the tap. Stop training so many PhDs.

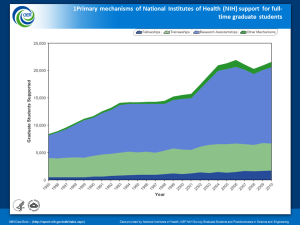

This is going to hurt the many, many of us (and therefore the NIH) who depend on the undervalued labor of graduate students. This chart (click to enlarge it) from the NIH RePORTER site shows the relatively slow increase in NIH funded fellowships and traineeships compared with the more rapid increase in research assistantships (light blue). Read: graduate students paid directly from research grants. The more graduate students we “train” in this way, the more we need to secure more R01s and other R-mech grants to support them.

This is going to hurt the many, many of us (and therefore the NIH) who depend on the undervalued labor of graduate students. This chart (click to enlarge it) from the NIH RePORTER site shows the relatively slow increase in NIH funded fellowships and traineeships compared with the more rapid increase in research assistantships (light blue). Read: graduate students paid directly from research grants. The more graduate students we “train” in this way, the more we need to secure more R01s and other R-mech grants to support them.

Spare me your anecdotes about how graduate students cost as much as postdocs or technicians (to your NIH R-mechanism or equivalent research grants). If they weren’t good value, you’d switch over. The system, as a whole, is most certainly finding value in exploiting the labor of graduate students on the promise of a career that is now uncertain to be realized. This is because the charging of tuition and fees is still incomplete. Because students have the possibility at some point during the tenure in our laboratories of landing supporting fellowships of various kinds. Because some departments still receive substantial Teaching Assistant funds to support graduate students (and simultaneously ease the work of allegedly professing Professors). And above all else, because we are able to pull off an exploitative culture in which graduate students are induced to work crazy hard in a Hunger Games style bloodthirsty competition for the prize….and Assistant Professor appointment.

It is going to hurt undergraduates who may wish to become PhDs and now cannot compete successfully for an admission to what are, presumably, going to become increasingly selective programs. I regret this. I am a huge fan of the democracy of our academic system and I wish to let all who have an interest…try. I have come to the belief that at this particular juncture, the costs are simply too high. The ratio of those who enter in pursuit of a particular outcome (Professordom) to those who achieve it is just too low. We need to rebalance. Part of the pain will fall on the undergraduate who wishes a career in science. Their chance to compete will be abrogated.

This is, in the short term, going to hurt the NIH’s output per grant dollar. Across the board, this labor is going to have to be replaced with research technicians*. People who get regular raises, benefits and work a more traditional number of hours per week.

But it will shrink the balloon of PhD trained people who are hankering to get into the NIH system as, eventually, grant-funded PIs. This will be a good thing in the end.

UPDATE 01/29/13: Check this out!

via ChemJobber

__

My honest disclosure is that this one is painless for past me and current me. First, I was a fairly decent candidate for graduate school when I applied. I looked good on paper, etc. I assume that I would still have been competitive for at least one of the four offers I received out of five applications. Second, I have made my way as an investigator without much reliance on graduate students labor. So for me, this one is painless. Shutting off the tap of graduate trainees wouldn’t have changed the way I have done research up to this point.

*One likely outcome is that graduate training and postdoctoral training is going to have to include more managerial approaches. Yes, this happens spottily across all of bioscience at present but as a population, it will increase. It will involve more supervision of techs earlier in the PhD training arc. I think this is a good thing.

An interesting historical note on the plight of younger investigators and the Ginther report

January 28, 2013

As noted recently by Bashir, the NIH response to the Ginther report contrasts with their response to certain other issues of grant disparity:

I want to contrast this with NIH actions regarding other issues. In that same blog post I linked there is also discussion of the ongoing early career investigator issues. Here is a selection of some of the actions directed towards that problem.

NIH plans to increase the funding of awards that encourage independence like the K99/R00 and early independence awards, and increase the initial postdoctoral researcher stipend.

In the past NIH has also taken actions in modifying how grants are awarded. The whole Early Stage Investigator designation is part of that. Grant pickups, etc.

…

I don’t want to get all Kanye (“NIH doesn’t care about black researchers”), but priorities, be they individual or institutional, really come though not in talk but actions. Now, I don’t have any special knowledge about the source or solution to the racial disparity. But the NIH response here seems more along the lines of adequate than overwhelming.

In writing another post, I ran across this 2002 bit in Science. This part stands out:

It’s not because the peer-review system is biased against younger people, Tilghman argues. When her NRC panel looked into this, she says, “we could find no data at all [supporting the idea] that young people are being discriminated against.”

Although I might take issue with what data they chose to examine and the difficulty of proving “discrimination” in a subjective process like grant review, the point at hand is larger. The NIH had a panel which could find no evidence of discrimination and they nevertheless went straight to work picking up New Investigator grants out of the order of review to guarantee an equal outcome!

Interesting, this is.

We are going to fix the NIH

January 28, 2013

Scicurious went to the trouble of Storifying a Twitter conversation that involved @mbeisen, YHN and @KateClancy, among others.

Kate Clancy provided more context for her outrage here in this post, Kate Clancy’s Short Grant Rant: On Broken Promises:

Last night I was talking to a colleague who just heard he missed the funding cutoff for his NIH grant by a single point – a score of 19 and under was funded, and his grant was a 20. He had applied to one of the many institutes that is trying to keep the R01 afloat by reducing funding to all the other funding mechanisms – which happen to be the mechanisms used more by early career faculty because they don’t have enough preliminary data for an R01 for several years.

Michael Eisen’s promised post is here, Restructuring the NIH and its grant programs to ensure stable careers in science:

It is an amazing time to do science, but an incredibly difficult time to be a scientist.

There is so much cool stuff going on. Everywhere I go – my lab, seminar visits, meetings, Twitter – there are biologists young and old are bursting with ideas, eager to take advantage of powerful new ways to observe, manipulate and understand the natural world.

But as palpable as the creative energy is, it is accompanied by an equally palpable sense of dread. We are in one of the worst periods of scientific funding I – and my more senior colleagues – can remember. People aren’t just worried about whether their next grant will get funded, they’re worried about whether a career in academic or public science is even viable

The very first post on the DrugMonkey blog read, in it’s entirety:

Biomedical research scientists in the US (and worldwide) are bright, highly educated and creative folks. Most are dedicated to the public good, undergoing years of low pay while fueling the greatest research apparatus ever built- the NIH-funded behemoth that is American health science. Yet they persist in various types of employment stress and uncertainty for years, with minimal confidence of ever attaining a “real job”. It is dismaying to realize that by the time he received his first R01 (the major NIH research grant) Mozart would have been dead for 7 years (tipohat to Tom Lehrer). The official noises coming from the National Institutes of Health, and even some individual institutes such as the National Institute on Drug Abuse (scroll for comments on the young investigator) are positive, sure. We’ve heard such sentiments before, however, and most objective measures show long, uninterrupted dismal trends for the young and developing scientist.

So yeah, my disclaimer is that I have some interest in efforts to fix some of the problems in the career arc of extramural NIH-funded science.

I anticipate that I may get even preachier than usual about these issues on the blog, encouraged by Michael Eisen’s post.

My aspiration is to damp down my tendency to snark and dismiss and exhibit a lack of patience with those who drag up the most obvious and tired points (soak the rich! too many overheads! greedy deadwood tenured jerks with 20 grants!). Feel free to hold me to that on posts tagged Fixing the NIH.

My request to you is to take your suggestions all the way down. Stand up for what you are really calling for. This means that you should identify who is going to pay the price for your fixes. What type of investigator, what generation of scientist, which types of University. Above all else, step up and admit when your policy plans

My request to you is to take your suggestions all the way down. Stand up for what you are really calling for. This means that you should identify who is going to pay the price for your fixes. What type of investigator, what generation of scientist, which types of University. Above all else, step up and admit when your policy plans are designed to conveniently also assist your situation now, in the past or in the future. I will endeavor to do the same.

There is a very simple truism of politics that never fails.

The Squeaky Wheel Gets the Grease.

Step up, my friends. Step up to the plate. Go over to Sally Rockey’s blog and throw down comment each and every time there is an opening. Write a letter to Science or Nature. Blog yourself. Write comments on blogs like Eisen’s, Clancy’s or mine. When you talk to your Program Officers at various Institutes or Centers of the NIH…slip in your points about careerism.

Don’t whine. Make it about science in your subdiscipline as much as you can and about your personal situation as little as possible. Quote facts about the NIH, preferably those they have generated themselves. Make specific proposals, constructive proposals and be honest about the impacts and implications.

Don’t whine. Make it about science in your subdiscipline as much as you can and about your personal situation as little as possible. Quote facts about the NIH, preferably those they have generated themselves. Make specific proposals, constructive proposals and be honest about the impacts and implications.

PSA: Beware the 'nip

January 25, 2013

Scientopia Schwaggage

January 25, 2013

I’m doing a face lift over at the Scientopia Blogs CafePress shoppe.

It’s been a little while since I messed around and they have a few new products including this little number for the #phitnessdouchery types. I realize I never really set this up beyond the basics so it may take me a little bit of time to put up the items that I think would be of interest. Meaning that in the event that you know there’s something in the cafepress catalog that I haven’t put up yet and you want it, drop me a note (drugmnky at the googles mail). I also tend to put images on the back of the shirt where cafepress permits. This is a personal preference. If you want something with the logo on the front drop me a line and we should be able to work that out.

It’s been a little while since I messed around and they have a few new products including this little number for the #phitnessdouchery types. I realize I never really set this up beyond the basics so it may take me a little bit of time to put up the items that I think would be of interest. Meaning that in the event that you know there’s something in the cafepress catalog that I haven’t put up yet and you want it, drop me a note (drugmnky at the googles mail). I also tend to put images on the back of the shirt where cafepress permits. This is a personal preference. If you want something with the logo on the front drop me a line and we should be able to work that out.

Oh, and I got around to making a DrugMonkey logo with the right URL on it finally. Here’s the much beloved simple coffee mug. I’ll get to the rest later.

Oh, and I got around to making a DrugMonkey logo with the right URL on it finally. Here’s the much beloved simple coffee mug. I’ll get to the rest later.

The only other news is that I’m adding a $0.50-1.00 markup which will be funneled back into the Scientopia operating fund. This is part and parcel of the effort previously leading to the paypal link and now the Google ads on the sidebar. We’re still running a hefty monthly deficit, this is being footed by one of the gang so anything you care to do to chip in will help out a ton.

College demographics

January 23, 2013

From the Atlantic:

Yes, yes, well I’m sure this is all because the pipeline is bad and we all know the blacks just aren’t very smart…

because after all…

huh. waitaminnit….something is odd…..

OMMFG!!!!!!!!!!!!1111!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Tragedy of the NIH Commons

January 23, 2013

From the San Diego Union Tribune:

…a fresh look under new Chancellor Pradeep Khosla. The discussions will last into next year and are likely to lead to expansion. Khosla has said that UCSD should be closer to UC Berkeley and UCLA when it comes to graduate student enrollment. About 30 percent of the students at those two schools are graduate students. The figure is roughly 20 percent at UCSD, and only about one-third of those students are Ph.D candidates.

Khosla told U-T San Diego that the campus probably could add 1,000 doctoral students at no additional cost because their tuition and stipends are paid from the research grants obtained by faculty. UCSD gets about $1 billion a year in research grants, ranking the campus among the top 10 nationally.

The part that I bolded tells the tale. The tale of our recent history during the NIH doubling in which all and sundry sought to increase their University standing and prestige “for free” on the Federal grant dime.

Khosla appears to be remarkably out of touch with current reality if he thinks this continues to be a winning strategy.

Perhaps he should survey his faculty and ask them who anticipates being able to swing more grad student positions (for 5-6 years) in the future based on their grants.

@mbeisen is on fire on the Twitts:

@ianholmes @eperlste @dgmacarthur @caseybergman and i’m not going to stop calling things as they are to avoid hurting people’s feelings

Why? Open Access to scientific research, naturally. What else? There were a couple of early assertions that struck me as funny including

@eperlste @ianholmes @dgmacarthur @caseybergman i think the “i should have to right to choose where to publish” argument is bullshit

and

@eperlste @ianholmes @dgmacarthur @caseybergman funding agencies can set rules for where you can publish if you take their money

This was by way of answering a Twitt from @ianholmes that set him off, I surmise:

@eperlste @dgmacarthur how I decide where to pub is kinda irrelevant. The point is, every scientist MUST have the freedom to decide for self

This whole thing is getting ridiculous. I don’t have the unfettered freedom to decide where to publish my stuff and it most certainly is an outcome of the funding agency, in my case the NIH.

Here are the truths that we hold to be self-evident at present time. The more respected the journal in which we publish our work, the better the funding agency “likes” it. This encompasses the whole process from initial peer review of the grant applications, to selection for funding (sometimes via exception pay) to the ongoing review of program officers. It extends not just from the present award, but to any future awards I might be seeking to land.

Where I publish matters to them. They make it emphatically clear in ever-so-many-ways that the more prestigious the journal (which generally means higher IF, but not exclusively this), the better my chances of being continuously funded.

So I agree with @mbeisen about the “I have the right to choose where I publish is bullshit” part, but it is for a very different reason than seems to be motivating his attitude. The NIH already influences where I “choose” to publish my work. As we’ve just seen in a prior discussion, PLoS ONE is not very high on the prestige ladder with peer reviewers…and therefore not very high with the NIH.

So quite obviously, my funder is telling me not to publish in that particular OA venue. They’d much prefer something of a lower IF that is better respected in the field, say, the journals that have longer track records, happen to sit on the top of the ISI “substance abuse” category or are associated with the more important academic societies. Or perhaps even the slightly more competitive rank of journals associated with academic societies of broader “brain” interest.

Even before we get to the Glamour level….the NIH funding system cares where I publish.

Therefore I am not entirely “free” to choose where I want to publish and it is not some sort of moral failing that I haven’t jumped on the exclusive OA bandwagon.

@ianholmes @eperlste @dgmacarthur @caseybergman bullshit – there’s no debate – there’s people being selfish and people doing the right thing

uh-huh. I’m “selfish” because I want to keep my lab funded in this current skin-of-the-teeth funding environment? Sure. The old one-percenter-of-science monster rears it’s increasingly ugly head on this one.

@ianholmes @eperlste @dgmacarthur @caseybergman and we have every right to shame people for failing to live up to ideals of field

What an ass. Sure, you have the right to shame people if you want. And we have the right to point out that you are being an asshole from your stance of incredible science privilege as a science one-percenter. Lecturing anyone who is not tenured, doesn’t enjoy HHMI funding, isn’t comfortably ensconced in a hard money position, isn’t in a highly prestigious University or Institute, may not even have achieved her first professorial appointment yet about “selfishness” is being a colossal dickweed.

Well, you know how I feel about dickweedes.

I do like @mbeisen and I do think he is on the side of angels here*. I agree that all of us need to be challenged and I find his comments to be this, not an unbearable insult. Would it hurt to dip one toe in the PLoS ONE waters? Maybe we can try that out without it hurting us too badly. Can we preach his gospel? Sure, no problem. Can we ourselves speak of PLoS ONE papers on the CVs and Biosketches of the applications we are reviewing without being unjustifiably dismissive of how many notes Amadeus has included? No problem.

So let us try to get past his rhetoric, position of privilege and stop with the tone trolling. Let’s just use his frothing about OA to examine our own situations and see where we can help the cause without it putting our labs out of business.

__

*ETA: meaning Open Access, not his attacks on Twitter

Cheating

January 21, 2013

Against my usual principles in such matters, I’ve been reading pro-cyclist Tyler Hamilton’s confessional book. It isn’t the finest writing in the world, as you might imagine. There are also a lot of specifics about particular races, events and participants/characters that will be of interest only to those who followed pro cycling during Tyler’s career.

Nevertheless.

There is a great deal of parallel here for the top level ranks of competitive sciencing. A great deal. And if we do not clamp down hard on where the Glamour Game has been taking science lately, this is where we are headed.

A place where “everybody is doing it, so we’re just leveling the playing field by photoshopping bands” is true, if not an excuse.

I suggest you read Hamilton’s book with a constant eye on science fraud.

GrantRant IX

January 20, 2013

If you are a BSD type who has had program pick up your grant despite a fairly critical and damning review….

Don’t come back after five years with the same flaws* in your application. Programmatic pickups are not validation that your grant writing was acceptable.

Feel fortunate that you got away with one and make sure that you do better next time.

Oh and you’d better produce. Reviewers are not going to look kindly on a renewal when the prior review was harsh and you haven’t knocked it out if the park scientifically.

__

*the number of times that I’ve seen this situation…… Amazing.