In hard times in NIH Grantlandia, guess who pays the steepest price?

January 13, 2014

A post over at Rock Talk blog describes some recent funding data from the NIH. The takeaway message is that every thing is down. Fewer grants awarded, fewer percentages of the applications being funded. Not exactly news to my audience. However, head over to the NIH data book for some interesting tidbits.

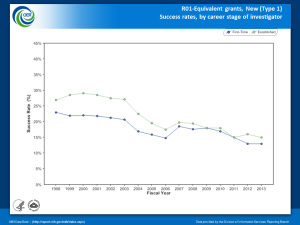

First up, my oldest soapbox, the new investigator. As you can see, up to FY2006 the PI who had not previously had any NIH funding faced a steeper hurdle to get a new grant (Type 1) funding compared to established investigators. This was despite the “New Investigator” checkbox at the top of the application and the fact that reviewers were instructed to give such applications a break. And they did in my experience….just not enough to actually get them funded. Study section discussion that ended with “…but this investigator is new and highly promising so that’s why I’m giving it such a good score…[insert clearly unfundable post-discussion score]” were not uncommon during my term of appointed service. So round about FY2007 the prior NIH Director, Zerhouni, put in place an affirmative action system to fund newly-transitioned independent investigators. There’s a great description in this Science news bit [PDF]. You can see the result below.

First up, my oldest soapbox, the new investigator. As you can see, up to FY2006 the PI who had not previously had any NIH funding faced a steeper hurdle to get a new grant (Type 1) funding compared to established investigators. This was despite the “New Investigator” checkbox at the top of the application and the fact that reviewers were instructed to give such applications a break. And they did in my experience….just not enough to actually get them funded. Study section discussion that ended with “…but this investigator is new and highly promising so that’s why I’m giving it such a good score…[insert clearly unfundable post-discussion score]” were not uncommon during my term of appointed service. So round about FY2007 the prior NIH Director, Zerhouni, put in place an affirmative action system to fund newly-transitioned independent investigators. There’s a great description in this Science news bit [PDF]. You can see the result below.

Interestingly, this will to maintain success rates of the inexperienced PIs at levels similar to the experienced PIs has evaporated for FY2011 and FY2013. See title.

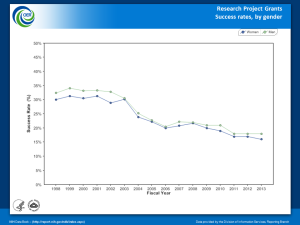

Next, the slightly more subtle case of women PIs. This will be a two-grapher. First, the overall Research Project Grant success rate broken down by PI sex. As you can see, up through FY2002 there was a disparity which disappeared in the subsequent years. Miracle? Hell no. I guarantee you there has been some placing of the affirmative action fingers on the scale for the sex disparity as well. Fortunately, the elastic hasn’t snapped back in the past two FYs as it has for inexperienced investigators. But I’m keeping a suspicious eye on it, as should you. Notice how women trickle along juuuuust a little bit behind men? Interesting, isn’t it, how the disparity is never actually reversed? You know, because if whomever was previously advantaged even slipped back to disadvantaged (instead of merely equal) the whole world would end.

Next, the slightly more subtle case of women PIs. This will be a two-grapher. First, the overall Research Project Grant success rate broken down by PI sex. As you can see, up through FY2002 there was a disparity which disappeared in the subsequent years. Miracle? Hell no. I guarantee you there has been some placing of the affirmative action fingers on the scale for the sex disparity as well. Fortunately, the elastic hasn’t snapped back in the past two FYs as it has for inexperienced investigators. But I’m keeping a suspicious eye on it, as should you. Notice how women trickle along juuuuust a little bit behind men? Interesting, isn’t it, how the disparity is never actually reversed? You know, because if whomever was previously advantaged even slipped back to disadvantaged (instead of merely equal) the whole world would end.

Moving along, we downshift to R01-equivalent grants so as to perform the analysis of new proposals versus competing continuation (aka, “renewal”) applications. There are mechanisms included in the “RPG” grouping that cannot be continued so this is necessary. What we find is that the disparity for woman PIs in continuing their R01/equivalent grants has been maintained all along. New grants have been level in recent years. There is a halfway decent bet that this may be down to the graybeard factor. This hypothesis depends on the idea that the longer a given R01 has been continued, the higher the success rate for each subsequent renewal. These data also show that a goodly amount of the sex disparity up through FY2002 was addressed at the renewal stage. Not all of it. But clearly gains were made. This kind of selectivity suggests the heavy hand of affirmative action quota filling to me.

Moving along, we downshift to R01-equivalent grants so as to perform the analysis of new proposals versus competing continuation (aka, “renewal”) applications. There are mechanisms included in the “RPG” grouping that cannot be continued so this is necessary. What we find is that the disparity for woman PIs in continuing their R01/equivalent grants has been maintained all along. New grants have been level in recent years. There is a halfway decent bet that this may be down to the graybeard factor. This hypothesis depends on the idea that the longer a given R01 has been continued, the higher the success rate for each subsequent renewal. These data also show that a goodly amount of the sex disparity up through FY2002 was addressed at the renewal stage. Not all of it. But clearly gains were made. This kind of selectivity suggests the heavy hand of affirmative action quota filling to me.

This is why I am pro-quota and totally in support of the heavy hand of Program in redressing study section biases, btw. Over time, it is the one thing that helps. Awareness, upgrading women’s representation on study section (see the early 1970s)…New Investigator checkboxes and ESI initiatives* all fail. Quota-making works.

__

*In that Science bit I link it says:

Told about the quotas, study sections began “punishing the young investigators with bad scores,” says Zerhouni. That is, a previous slight gap in review scores for new grant applications from firsttime and seasoned investigators widened in 2007 and 2008, Berg says. It revealed a bias against new investigators, Zerhouni says.

January 13, 2014 at 3:10 pm

Don’t forget K awards too. Their numbers have dropped fairly substantially in recent years, as has the success rates. I would argue that this is just as important in terms of helping young scientists just get a foot in the door.

What is also interesting/depressing is that the number of PhDs awarded on the NIH dime is still increasing linearly as far as I can tell from the data book, as is biomedical graduate school enrollment. This despite all other funding trends suggesting that the opposite should probably be happening. Isn’t this the real problem that the NIH will face? Total PhDs awarded surely should reflect (at least) the funding situation at the top of the pyramid. Where are all these people going to go?

LikeLike

January 13, 2014 at 3:36 pm

not linearly, no. Check out this chart from the Data Book.

It does show that there was a huge increase in graduate students supported on research assistantships associated with the doubling. Seems obvious that number should crash back to the trend established pre-doubling, since the purchasing power of the NIH has done so.

LikeLike

January 13, 2014 at 3:57 pm

I’m looking at this figure and focusing on total enrollment. It only goes up to 2011.

http://report.nih.gov/NIHDatabook/Charts/Default.aspx?showm=Y&chartId=228&catId=19

LikeLike

January 13, 2014 at 5:27 pm

But to extend this logic, if we should reduce the flow of incoming grad students to stem oversupply, shouldn’t we also reduce grants to ESI’s to prevent there being too many mouths at the trough?

LikeLike

January 13, 2014 at 6:30 pm

Where are all these people going to go?

In a van down by the river, that’s where.

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 5:10 am

Exactly, DJMH. The ‘encouragement’ has to stop somewhere. In fact, it could be argued that the best place to minimize NIH support is at late-stage postdoc (K-award, etc) and at the early stage of PI careers (before they get any sort of tenure).

Why not minimize grad students and Ph.D.s? Because it could be argued that they can go on to other (non NIH trough) careers. And we seem to need them, given the low PhD unemployment.

Why not minimize support for established investigators? Because they’re in the system anyway. We can’t change that. We need to wait for them all to die.

Late stage postdocs and early stage investigators need to be shown the exit. Cruelly if necessary. Or the ‘glut’ will continue.

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 6:54 am

In fact, it could be argued that the best place to minimize NIH support is at late-stage postdoc (K-award, etc) and at the early stage of PI careers (before they get any sort of tenure)

As DM pointed out here, that is already happening (look at the figures for ESIs). K-awards have also taken a fairly decent hit in recent years, as you can see from the data book. But you are right, these things probably needed to happen on some level. The issue seems to be that graduate enrollment appears immune to NIH budgetary pressures.

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 7:04 am

DJMH, TOD- sure, you can argue that we should stop with the ESI help. The PHD overproduction is a longer term fix, I will admit. I don’t personally favor your approach because I am looking at a generational imbalance caused by the Baby Boomers and I think that a more even distribution of ages in the system would be best. To me there is value in each career stage but if one slice comes to dominate it distorts the future conduct of science.

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 8:00 am

All of this talk of quotas in the beginning and then the comments say things like this:

Late stage postdocs and early stage investigators need to be shown the exit. Cruelly if necessary. Or the ‘glut’ will continue.

Lets keep the quota idea in our heads when we start talking about thinning the herd.

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 8:11 am

Opinions vary, Steve Todd.

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 8:43 am

I don’t know the answer, but what happens to degree accreditation in the PhD tap is turn off? Wouldn’t a bunch of separate departments cease to exist?

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 10:15 am

So any adjustments to funding policy should be aimed not at ensuring a sustainable scientific enterprise, but at keeping the bloat that is already there (fund established investigators until they all die) and making sure that no pushy and potentially more competitive people try to displace them, this last part achieved by pulling the rug from under ESIs/late PD while they are still vulnerable. Am I hearing this right?

I’d argue that if the overall goal of the NIH gravy train is to provide a product that the american taxpayer is willing to purchase, then the “glut” is excess capacity regardless of the career stage. I don’t think that because I’m ESI I’m any more “glutty” than more established folks. If the funding contraction is experienced evenly across the board for a sustained period the problem should solve itself. The help for NI/ESIs, as I understand it, is meant to compensate for unfair evaluation, so it’s necessary for the “evenly” part.

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 11:12 am

No discussion in this realm would be complete without addressing the issues surrounding “cheap labor,” in the form of graduate students and postdocs. Who will be doing the pipetting, and how much should they cost? If you are a bright 20-something with an undergrad science degree who happens to be unemployed, grad school and a stipend looks pretty good, despite the potential for exploitation and the low chances of landing a faculty job in academia.

At the top-tier medical school I am most familiar with, the new assistant professors benefit greatly from the availability of cheap labor in the form of grad students supported by large training grants. In some cases, the only thing that saved them from not getting tenure was a body of exceptional work from one or two highly-motivated students, who were cheap enough to pay on a startup plus a couple of foundation grants. This led led to publications, and formed the basis of successful R01 applications and tenure.

Has anybody ever calculated the percent of US grad students and postdocs that were not born in the USA? I reckon it is well over 50% today. Why? Because a whole lot of native-borns have seen the writing on the wall and chosen different careers, and those slots have been filled with immigrants. Most immigrant trainee-scientists I’ve worked with are extremely bright and exceptionally motivated. Any cut in the number of trainee slots has far-ranging consequences. The best and brightest will go elsewhere when the pyramid scheme collapses.

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 11:42 am

Has anybody ever calculated the percent of US grad students and postdocs that were not born in the USA?

Jeeez, do people not look at the data book? Here is what you are looking for:

http://report.nih.gov/NIHDatabook/Charts/Default.aspx?showm=Y&chartId=251&catId=19

http://report.nih.gov/NIHDatabook/Charts/Default.aspx?showm=Y&chartId=259&catId=20

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 11:53 am

Wouldn’t a bunch of separate departments cease to exist?

Only if they found themselves to be unviable at a reduced size. (let’s face it, actually shuttering programs is more of a pipe dream than reductions.) But still, a degree doesn’t cease to exist if the department/program that granted it 10 years ago stops awarding PhDs, right?

fund established investigators until they all die

that flat lining of established investigator success rates across the past three FYs is certainly notable. Unfortunately we don’t know which slice of the established is benefiting. Maybe it is all going to the recently-ESI, eh?

the new assistant professors benefit greatly from the availability of cheap labor in the form of grad students supported by large training grants.

Attention, all ye who claim that “grad students are just as expensive as techs or postdocs”.

Has anybody ever calculated the percent of US grad students and postdocs that were not born in the USA?

Ask, and ye shall receive. [biomed only]

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 1:11 pm

“Only if they found themselves to be unviable at a reduced size. (let’s face it, actually shuttering programs is more of a pipe dream than reductions.) But still, a degree doesn’t cease to exist if the department/program that granted it 10 years ago stops awarding PhDs, right? ”

True but I think the powers that be would start looking for a way to consolidate said department with another that is granting degrees.

One of my home institution’s goals is to increase the number of PhD students over time. Shortsighted as it is, it’s right there in the strategic plan. In order to stymie the constant influx of students from our interdisciplinary program, my department raised the bar for the PhD qualify exam so astronomically high that it scared off many of the new students into other departments. Problem solved.

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 1:27 pm

The following is my personal opinion as a private citizen and does not represent anyone or anything else.

I think you’re off base if you think giving more power to program will address the problem. Mainly because program is, in fact, part of the problem. That’s not to say there aren’t program officers who are sympathetic. But I’ve heard way too many conversations about how to avoid funding or modify the presentation of certain kinds of “controversial” research that get good scores for political reasons or out of fear of media blowback, noticed that diversity supplement applications always seem to be rejected by program for “good reasons” or reviews delayed for months because the application was forgotten , or program officers not getting that inclusion mattered for clinical trials (to be fair, many PIs don’t get the point of this either).

I don’t know the solution, but selective funding only works if the NIH wants to address the problem.

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 2:04 pm

noticed that diversity supplement applications always seem to be rejected by program for “good reasons”

That is interesting. My ICs of greatest relevance and familiarity seem to be always eager to fund diversity supplements and mention that they do not get enough of them submitted.

selective funding only works if the NIH wants to address the problem.

Agree. The point of my ranting is to rally up some shaming behavior. The problem with your anti-Program stance is that study sections are inherently conservative beasts. It’s structurally built in. Program input is the only current counterweight to this.

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 3:08 pm

My anecdotal experience is limited to a couple ICs (and it wouldn’t surprise me if it varies–there are 27 ics and centers after all with 27 different directors), but, yes, my experience is not a lot of applications come in. On the other hand, of those that do, not too many are funded (and several that do just to close out the budget at the end of the year). I am not a scientist so whether the reasons for not funding are good or not I leave for others to judge.

I also wouldn’t say my stance is anti-program (in my experience, people outside tend to overestimate how much input program actually has–although it varies from IC)–more frustration with the culture and my own powerlessness to change it. Plus, I know program much more than review.

LikeLike

January 14, 2014 at 4:07 pm

In some time in the future, I would hope to see the abolition of the tenure and the PhD altogether as institutions. Academic Freedom suffers from these outdated institution. Combined with the favoritism of funding bodies like NIH, academic freedom is a farce. Think about how that may come about. The maker movement and citizen science offer clues if imperfect and “prehistoric”.

LikeLike

January 15, 2014 at 4:45 am

Bruno — Tenure is actually useful for standing up to administrative abuses. There are almost no real measures of academic ‘worth’ other than the reputation among peers. Thus, if one fears losing one’s job too much, academia will devolve (even more than it is) into one giant ass-sucking ring. Tenure permits at least some integrity and originality.

That said, I agree that a lot of people also use it as protection for their own arrogant laziness.

With regard to funding, tenure probably improve the quality and integrity of externally funded science. There is tremendous pressure for pre-tenure researchers to fake data to stay employed. I’m not a fan of soft-money positions either. I think that’s an institutional cop-out and increases the pressure for research fraud.

LikeLike

January 15, 2014 at 6:19 am

I think that’s an institutional cop-out…

True statement.

LikeLike

January 17, 2014 at 9:42 pm

Maybe the study section judging ESI applications should have more ESI investigators. Very often ESI people are fresh out of bench or still at bench and more focus on techniques while greybeards are far removed from the bench so trash applications that look like more technical.

LikeLike

January 18, 2014 at 5:26 am

All study sections should have some ESI participation.

LikeLike

January 18, 2014 at 5:27 am

And by “some” I mean in approximately equal proportion to the applications submitted at the very least.

LikeLike

January 18, 2014 at 7:09 am

Good luck with that, DM. I doubt this will happen anytime soon. Academia is deeply hierarchical.

LikeLike

March 18, 2014 at 10:53 pm

The way to deal with a tenure and phd-less science demands a complete restructuration of research. Not implausible but hard, “revolutionary”. The first institution for a new mxm for protecting freedom is a common lab workspace, funded collectively, that holds a department’s basic facilities, universally accessible, and endowed with some operation cost overhead. The free scientist can operate within this commonwealth and publish. Think of it as a universal healthcare-like subsection of any department. Science socialism. A playground for students and juniors (keeping in mind that phd and tenure have been largely abolished. ) a second idea that’s interesting came from 2 Canadian scientists; simply give equal funds to all scientists, but with the condition that they must give x % to other scientists. Thus funding becomes utterly decentralized. The sources of funding become nearly infinite. Of course there are gotchas that would require rules. Could be actually fun.

LikeLike