Repost: Estimating the Purchasing Power of the NIH Grant

December 17, 2013

A query on the Twitts today:

https://twitter.com/Dr24hours/status/412950836298272768

reminded me of this post. It originally went up 12 July, 2012.

This reality is echoed in personal anecdote. If I look across my grant submissions within a particular part of the lab over the years, I am more or less proposing the same scope of work in each R01. I started submitting grants within the first few years of the modular budgeting era and was matching my proposals to what could be accomplished within the $250K limit. Time marched on…but it took me a long time to cotton on to the purchasing power issue. I just squeezed and tried to compensate by proposing new projects. Because of the considerably reduced hit rate, I’ve taken to doing traditional budgeting lately. And, what do you know? It comes in at about $375K. Same scope as I used to fit within the $250 limit.

You are probably aware, DearReader, of the concept of inflation. This means that the amount of money that you pay today for a good or service is higher than the amount of money that you paid yesterday.

On average.

So for example, this US inflation calculator tells me that the purchasing power of $12,000 in 1972 has the purchasing power of $65,975.60 in 2012. This is a convenient set of figures if, for example, you are shooting the breeze with a senior faculty member* who started his or her Assistant Professor appointment in the early 70s. You may want to grapple with pay on even terms. Naturally, not every good or service has the same inflation rate and this is just one model/estimator. Jeans may cost less and houses may cost more. etc.

Moving along, we come to the discussion of NIH Grants. In the past I’ve posted the analysis that shows that the doubling of the NIH budget was rapidly un-doubled and fell back on the historical trend line. [see update suggesting we are now defunding the NIH] That analysis depended on the Biomedical Research and Development Price Index or BRDPI. This brings us to an interest in the purchasing power of the full modular R01. “Modular” refers to the specification of the budget for most NIH grant types in units of $25,000 in direct costs. These are the “modules”.

There has been a cap of $250,000 per year in direct costs since the 6/1/1999 initiation of this structure, if I have that right. You can ask for more money per year but then you revert to a line-item type budget (called “traditional budgeting”). The modular cap has not changed and, I assert, this limit affects the vast majority of NIH R01 proposals since there is high motivation (or has been, I may have touched on reasons for future changes before) to adhere to the modular grant structure. Overall, I do like the notion of the modular budgeting procedures because it keeps reviewers from ticky-tacking a bunch of irrelevancies about grants when they should focus on the science.

However, the use of a limit like this brings up the unpleasant inevitability of inflation.

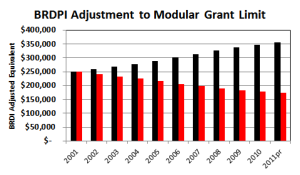

Comrade PhysioProf has been noting that the real purchasing power of the R01 has been dropping due to inflation in the context of postdoctoral fellow demands for ever increasing salaries. He’s not alone in noticing. I offer today, a graphical depiction pulled from data provided by the NIH Office of Budget on the BRDPI.

I”ve taken their table of yearly adjustments and used those to calculate the increase necessary to keep pace with inflation (black bars) and the decrement in purchasing power (red bars). The starting point was the 2001 fiscal year (and the BRDPI spreadsheet is older so the 2011 BRDPI adjustment is predicted, rather than actual). As you can see, a full modular $250,000 year in 2011 has 69% of the purchasing power of that same award in 2001.

I”ve taken their table of yearly adjustments and used those to calculate the increase necessary to keep pace with inflation (black bars) and the decrement in purchasing power (red bars). The starting point was the 2001 fiscal year (and the BRDPI spreadsheet is older so the 2011 BRDPI adjustment is predicted, rather than actual). As you can see, a full modular $250,000 year in 2011 has 69% of the purchasing power of that same award in 2001.

For those looking at the increasing numbers of applications being submitted presented in the prior post, you must include some understanding of this inflationary pressure in your thinking.

The second thing we’ve found here is the target number to restore spending parity.

In simple terms, we should now be advocating for an increase to $350,000 as the new modular cap.

__

*Particularly handy when said senior (or emeritized, retired) faculty members are members of one’s own family. just sayin.

December 17, 2013 at 7:42 am

Yup, it’s all shoveling shit against the tide.

LikeLike

December 17, 2013 at 8:48 am

My question: more grants with lower amounts, or fewer grants with higher amounts?

LikeLike

December 17, 2013 at 8:53 am

My question: more grants with lower amounts, or fewer grants with higher amounts?

Depends on who you are I suppose. I work pretty cheap, so I’d prefer more grants funded at lower $$, but I’m pretty sure that DM would prefer the opposite.

LikeLike

December 17, 2013 at 11:02 am

While collapse of R01 purchasing power is a real problem, doesn’t the graph artificially inflate the issue in its visual presentation? The graph asks us visually to compare black bar to red bar – but that accounts for inflation twice, since each set of bars is a separate inflation measure; once positively in the black bar, once negatively in the red bar. So visually, it appears that we are at 50% of equivalent-dollar-value per R01, rather than the 69% in the text.

My impression is that the third factor is increases to the cuts to the granted (rather than requested) modular budget – that PIs used to receive a larger percentage of the requested modular R01, such that R01 purchasing is now eroded by more than inflation. Do we have any data on that?

LikeLike

December 17, 2013 at 11:22 am

If equipment >$5,000 was qualified as capital equipment, this number needs to be increased to $6,583.87 for 2013. NIH is simply failed to acknowledge inflation. Is everyone at the NIH getting any pay raise throughout the years to compensate for the inflation at all?

LikeLike

December 17, 2013 at 12:00 pm

My question: more grants with lower amounts, or fewer grants with higher amounts?

From a system perspective (i.e., the NIH one) I would think you would look for efficiency. How many labs do you have that average about X amount of Direct Costs over the long haul? Are these what you think of as your most productive labs? If so, how do you get these *types* of labs their money as efficiently as possible? What do you “risk” by allocating larger chunks at a time (as was the case in the past)?

If you had really slick modelers, you might even be able to launch down each individual lab’s trajectory and look for how much money caused a lull in their submission rate.

LikeLike

December 17, 2013 at 12:01 pm

The graph asks us visually to compare black bar to red bar

No, it doesn’t.

LikeLike

December 17, 2013 at 12:04 pm

Do we have any data on that?

Nothing collected that I have seen. If everyone goes and comments on Rockey’s blog asking for dollars requested versus dollars awarded maybe we’ll get something. My vague memory is that the only time they’ve done such a thing the “requested” came from all grant submissions, not the ones they’d selected for funding.

LikeLike

December 17, 2013 at 5:59 pm

I still say the bigger problem is the lack of reliable renewal. There was a time when you could live on one grant, renewed every five years. That meant a much healthier work-on-science to work-on-grants ratio. Increasing the modular grant size isn’t going to change the variability problem. Losing $350k isn’t any better than losing $250k…

The real problem is that you can’t PLAN anymore.

LikeLike

December 17, 2013 at 7:23 pm

Oh, you can PLAN all you want. You just have to consider “losing my job because I lost my grant and can’t get another one” in your plans.

LikeLike

December 18, 2013 at 5:56 am

“Depends on who you are I suppose. I work pretty cheap, so I’d prefer more grants funded at lower $$, but I’m pretty sure that DM would prefer the opposite.”

I think it wouldn’t be such a bad idea to implement an incentive structure that encourages small town grocers (of which I’m one) to apply for a different stream of money in a move to get them out of the competition for the big bucks. At the moment, institutional pressure and the archaic and increasingly ridiculous notion that faculty should always be training grad students is causing at least some labs (hard to say how many) to operate on more money than they probably really need to meet the objectives of the proposals they submit.

It also wouldn’t be a bad idea to have a mechanism in which PIs compete like contractors, where the requested budget as well as the quality of the proposal are taken into account. I get the philosophical reasons for largely keeping budget issues out of grant review, and this should be preserved for RO1s, but I think there’s something to be said for encouraging a wee bit of free market fever into at least some aspects of funding given the way things are now. It wouldn’t hurt if a PI who can get the work done without hiring new personnel could be allowed a distinct advantage over a PI requesting a postdoc to do the same sort of project.

LikeLike

December 18, 2013 at 10:19 am

Losing $350k isn’t any better than losing $250k…

You are missing the point. If the historical averages, and the rationale for selecting the $250K per year cutoff, are worth anything then it suggests that even the one-grant/continued-forever lab you reference has to be a 1-point-something lab. One grant isn’t enough anymore. Raising the modular limit to $375K (with bump-ups due to inflation planned every 7 years) might relieve this pressure. Thus, it would reduce the churn. If a given lab doesn’t need the full amount, fine, they can ask for fewer modules and as dsks suggests, maybe Program will decide to start taking overall cost into account (they actually do this already when making out-of-order pickups, of course).

LikeLike

December 18, 2013 at 11:13 am

So, fewer but fatter grants? Because to keep funding at current number of awards with a 50% increase in the modular budget (and associated indirects) would require an extra 5 billion, and I don’t see congress in a generous mood.

LikeLike

December 18, 2013 at 11:29 am

So, fewer but fatter grants?

Yes. I think this would help tremendously with the churn and stability issues.

Keep in mind that we are still waiting to see good per-investigator numbers out of the NIH.

Fewer *grants* awarded does not necessarily mean fewer *investigators* in any direct sense. Particularly in the context of this discussion about the purchasing power of one “grant”, i.e., the full-modular R01.

LikeLike

December 18, 2013 at 12:14 pm

DM:“One grant isn’t enough anymore. “

…only if you propose the same amount of research per year. But that amount of research is completely arbitrary. People can scale back. Or work cheap.

I personally like that there is some pressure to work cheap. As you said, DM, there is some psychological incentive to stay under a modular budget. But there is no incentive to ask for less than the full number of allowed modules. Thus, I think raising the modular budget cap will just encourage waste.

And seriously… think about it. Should we really be allowed to ask for more than a quarter of a million dollars a year without justifying it? Asking for less accountability seems a bit tin-eared, given the national budget situation.

LikeLike

December 18, 2013 at 12:21 pm

“Fewer *grants* awarded does not necessarily mean fewer *investigators* in any direct sense. “

How do you figure that, given that the average number of R01s per investigator is ~1.2-1.4?

And given that the average request is already almost half a million dollars, do you think changes to the modular budget would even make a difference?

(My assertions are based on Rocktalk blog data)

LikeLike

December 18, 2013 at 12:36 pm

But that amount of research is completely arbitrary. People can scale back.

That is not really true. There are quantal costs for research as well as some serious economies of scale*. And there are expectation for yearly productivity and what will get a decent score in a 5 year plan. Sure there is a lot of variance across subdisciplines but the idea that anyone in a given situation can just “scale back” is false.

*A tech, phd student or postdoc costs X amount for the year. It is most usual in my fields of interest that one lab pays this cost for a whole person. If grant support ebbs, it is most usual that a person is dropped entirely rather than being placed on part time status. As I’ve noted before, if you have two grants and need three people then when you go down to one grant you can’t go to 1.5 people. You go to 1 person. Cut of a $25K module isn’t an *entire* salary but again, you can’t cut to 75% of a person..you cut the whole person.

Nonpersonnel costs can be a bit more easily scaled but you run into problems of inefficiency quite quickly. If I have a person in my lab running rats in operant boxes, say, then we could in theory “scale back” by running fewer experiments per year and paying less in animal costs. but then I’m burning person time with less efficiency.

LikeLike

December 18, 2013 at 12:42 pm

How do you figure that, given that the average number of R01s per investigator is ~1.2-1.4?

Because my analysis is about only that population that is saying, by their grant writing behavior, that their labs need more than one grant. Also this is defined by the behavior of study sections and Program that those programs *deserve* more than one grant.

Since there is no requirement to ask for the full amount, there is no need for those people in the one grant category to ask for, or be awarded, more than $250, right? 🙂

And given that the average request is already almost half a million dollars, do you think changes to the modular budget would even make a difference?

are you confusing DC and IDC? What average “request”?

LikeLike

December 19, 2013 at 3:08 am

As DM and CPP have both said many many times, the main reason you need two grants is so that your lab doesn’t shut down when one fails. The main reason my colleagues struggle mightily for more than one grant is so that they can be staggered and you can keep some money flowing, even while trying to renew.

Raising the modular limit to $350k is not going to help this problem. In fact, if anything, I think it will hurt because it is going to decrease the number of grants available. (If you multiply each grant by 1.5x, you have to divide the total number available by 1.5x.) Increasing the limit to $350k is going to increase the correlation of one’s funding, so that it all arrives at the same time (when you finally hit that $350k) and all vanishes at the same time (when you are struggling to renew that $350k). That’s only going to make the real problem worse.

Although I understand that there are fields where $350k is the minimum, that’s simply not true in many fields. I think that $250k is working fine (at least it is in the several fields I run in) and if someone asks for $350k with justification, no one really balks. (Asking for $450k without justification… now that’s a different story.) My main point is that this is not the real problem with NIH right now. The real problem is the lack of consistency, which prevents the one-R01-lab that we used to be able to run, which means that a lot of people who would do better running a small lab are forced to run big labs. People need to be able to find their maximal productivity. For some that’s a small, tight operation. For others, that’s a big, spread operation.

What we need are both small-lab-operators and large-empire-builders. We need to make both viable. Right now, the small-lab operation is not a viable path.

LikeLike

December 19, 2013 at 6:15 am

I think qaz nails it. I am also not so excited about the idea of giving more to fewer.

I get what you’re saying, DM, about personnel costs being somewhat fixed and inflexible. But that’s only true if you’re wedded to American-style scientific management. A lot of the European labs I’ve worked in/with lately are part of institutes with a lot of shared resources, including people. Techs usually work for many labs, and even postdocs seem to cycle in and around supported by many smaller sources of funding. In such a situation, you CAN scale back to 75% of a tech, or a postdoc. Someone else just picks up the rest of the person’s time. What I like about it from a PI perspective is that there always seems to be a continuously available pool of deep expertise around. When you need it, you just dip into that pool. The bad side is that there are often deeply embedded hierarchies and institutional politics that need navigating. But overall I think more shared personnel is a viable efficient option that I wish were more common in the U.S. Perhaps some European readers could chime in here?

LikeLike

December 19, 2013 at 12:56 pm

I don’t dislike your proposal here TOD, but it is going to take some very painful differences in the way we do business. Around my parts, anyway.

In the majority of cases I know of that work approximately like this it is because one BigCheez investigator has a LOT of grant money. This person then becomes the default home of shared talent which is farmed out by %ages to individual local projects at times.

LikeLike

December 19, 2013 at 6:42 pm

This is not probably the right place to ask this question, but it would be great if anyone could give me suggestions.

My grant supplement was reviewed by a study section (summer) and council (fall) and the PO told me that the proposal would be funded. The grant was planned to start in December, but I have not heard any from NIH. When I asked the PO about my grant via email twice recently, he did not respond.

What might this mean? Why does the PO ignore my emails? What should I do with the situation? Your comments would be appreciated. Thank you.

LikeLike

December 20, 2013 at 5:10 am

Read this and the link on December 1 start dates, red.

http://scientopia.org/blogs/drugmonkey/2010/12/03/congressional-inaction-continuing-resolutions-and-new-nih-grants/

Tl;dr “Blame Congress”

LikeLike

December 20, 2013 at 7:04 am

Re: DM Dec 19 12:56PM…

Yes, DM, I agree. Those are the conditions I see it too. And actually, now that I think about it, it’s not so different in Europe. The ‘BigCheez’, in that case, is the institute director — basically a huge group administrator. The PIs there are the equivalent of research faculty here. Except the good thing there is that the workers are technically employed by the institute, not a PI, and this relationship is formalized as such. it’s common there, for example, to hear postdocs say they work ‘at the XXX Institut, on blalahblah’. Whereas here, people tend to say they’re ‘a postdoc in soandso’s lab’.

My impression is also that salary money and money for the science is disconnected more in Europe. The granting agencies fund people. And projects. But people are not part of projects. Here in the U.S., the personnel are basically like reagents you buy.

LikeLike

December 21, 2013 at 2:51 am

Thank you Drugmonkey for your response.

LikeLike

December 21, 2013 at 7:13 am

TOD- yeah that’s pretty much how the Germans run things, at least.

I would add: it’s really, really hard to fire people in Germany. This can be a problem- lots of dead wood in departments, etc. And, there’s been some backlash from the Big Cheeze PIs- they don’t hire until you’ve done a 3 to 6 month trial run. This has lead in turn to younger scientists getting strung along on very short contracts, even when it’s clear they can do the job, to maintain control.

I’d personally like to see a system where you get 5 to 7 year contract after a trial run- and, further long term renewable contracts based on productivity over that period. Nothing overly unrealistic- good work done in working journals, or patents; or even highly successful students that benefited from your mentorship.

Also, you can include % salaries for staff in German grants; but I think this depends on the funding agency. I did ask why no-one had written an R01 for the Raman & IR microscopes I put in at a hospital over there. Found that the grant only covered the purchase of the instruments- not anything for personnel to actually run them. It’s kind of a weird situation in Germany; there’s a reason their more talented younger PI-types tend to leave the country. Seniority tends to garner more respect than talent.

LikeLike