Shut off the PhD tap

January 28, 2013

We need to stop training so many PhD scientists.

It is overwhelmingly clear that much of the quotidian difficulty vis a vis grant funding is that we have too many mouths at the NIH grant trough. The career progression for PhDs in biomedicine has experienced a long and steady process of delay, impediment, uncertainty and disgruntlement, things have only gotten worse since this appeared in Science in 2002.

The panel’s co-chair, biologist Torsten Wiesel of Rockefeller University in New York City, is surprised to learn that this aging trend continues today: “You’d think with all the money that’s going into NIH, [young scientists] would be doing better.” His co-chair, biologist Shirley Tilghman, now president of Princeton University, says simply, “It’s appalling.” The data reviewed by the panel in 1994 looked “bad,” she says, “but compared to today, they actually look pretty good.” She adds: “The notion that our field right now has such a tiny percentage of people under the age of 35 initiating research … is very unhealthy and very worrisome.” …Experts differ on why older biomedical researchers are receiving a growing share of the pie these days and on what should be done about it. But they agree on the basic problem: The system is taking longer to launch young biologists.

We need to turn off the tap. Stop training so many PhDs.

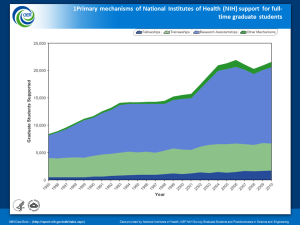

This is going to hurt the many, many of us (and therefore the NIH) who depend on the undervalued labor of graduate students. This chart (click to enlarge it) from the NIH RePORTER site shows the relatively slow increase in NIH funded fellowships and traineeships compared with the more rapid increase in research assistantships (light blue). Read: graduate students paid directly from research grants. The more graduate students we “train” in this way, the more we need to secure more R01s and other R-mech grants to support them.

This is going to hurt the many, many of us (and therefore the NIH) who depend on the undervalued labor of graduate students. This chart (click to enlarge it) from the NIH RePORTER site shows the relatively slow increase in NIH funded fellowships and traineeships compared with the more rapid increase in research assistantships (light blue). Read: graduate students paid directly from research grants. The more graduate students we “train” in this way, the more we need to secure more R01s and other R-mech grants to support them.

Spare me your anecdotes about how graduate students cost as much as postdocs or technicians (to your NIH R-mechanism or equivalent research grants). If they weren’t good value, you’d switch over. The system, as a whole, is most certainly finding value in exploiting the labor of graduate students on the promise of a career that is now uncertain to be realized. This is because the charging of tuition and fees is still incomplete. Because students have the possibility at some point during the tenure in our laboratories of landing supporting fellowships of various kinds. Because some departments still receive substantial Teaching Assistant funds to support graduate students (and simultaneously ease the work of allegedly professing Professors). And above all else, because we are able to pull off an exploitative culture in which graduate students are induced to work crazy hard in a Hunger Games style bloodthirsty competition for the prize….and Assistant Professor appointment.

It is going to hurt undergraduates who may wish to become PhDs and now cannot compete successfully for an admission to what are, presumably, going to become increasingly selective programs. I regret this. I am a huge fan of the democracy of our academic system and I wish to let all who have an interest…try. I have come to the belief that at this particular juncture, the costs are simply too high. The ratio of those who enter in pursuit of a particular outcome (Professordom) to those who achieve it is just too low. We need to rebalance. Part of the pain will fall on the undergraduate who wishes a career in science. Their chance to compete will be abrogated.

This is, in the short term, going to hurt the NIH’s output per grant dollar. Across the board, this labor is going to have to be replaced with research technicians*. People who get regular raises, benefits and work a more traditional number of hours per week.

But it will shrink the balloon of PhD trained people who are hankering to get into the NIH system as, eventually, grant-funded PIs. This will be a good thing in the end.

UPDATE 01/29/13: Check this out!

via ChemJobber

__

My honest disclosure is that this one is painless for past me and current me. First, I was a fairly decent candidate for graduate school when I applied. I looked good on paper, etc. I assume that I would still have been competitive for at least one of the four offers I received out of five applications. Second, I have made my way as an investigator without much reliance on graduate students labor. So for me, this one is painless. Shutting off the tap of graduate trainees wouldn’t have changed the way I have done research up to this point.

*One likely outcome is that graduate training and postdoctoral training is going to have to include more managerial approaches. Yes, this happens spottily across all of bioscience at present but as a population, it will increase. It will involve more supervision of techs earlier in the PhD training arc. I think this is a good thing.

January 28, 2013 at 10:25 am

With sincere and well-earned respect @drugmonkeyblog, that is a stupid idea. #NIH #NIHGrants

Once you’ve stopped the tap, how do you propose you get it started again?

“Look at how good India is at it? Why should we bother? It’s so exhausting being the leader?”

Why not turn off the spigot earlier? Sci college degrees? Kids are just going to feel badly if they can’t go on to get a PhD, so we’d be doing them a favor!

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 10:38 am

Once you’ve stopped the tap, how do you propose you get it atarted again?

Please. I’ve seen graduate programs bounce around by a factor of 3-5 in terms of new admits from year to year. If we drop existing program admits by half or three quarters there is no problem whatsoever multiplying that by 4 or 5-fold at any conceivable point in the future. If anything, the increased competition for slots will drive up the pent-up demand…kind of like medical school admissions….and “recovery” will be a snap. in, you know, the very unlikely future in which we (the US taxpayers) decide to fund more science.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 10:51 am

Part of the work for this (and for shrinking the NIH) must be done within our uni’s. If Harvard says “let Yale do this” and if U of Middle Nowhere Flyover says “I can’t afford to do this else no one notices me” it won’t work. It will always be someplace else or someone else. The change needs to be desired by the Dean-level admin- where they recognize what constitutes good science. I still believe that a large chunk of the problem is the enormous size of the BSD med schools so that all that gets noticed as statistics, h-indices, IF’s and number and amount of grants. If you administer/govern/rule by the numbers, cutting anything will be an anathema.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 10:52 am

Not sure it needs to be shut off so much as limited:

1. No research grant money can be spent on Phd student stipend/tuition

2. Either PIs apply for separate training grants to support students (then hire them themselves rather than the stupid F32 review system), with limits set on trainees/$, or training grants come as earmarks on research grants, e.g. 2 trainees (student or postdoc) per R01. Either way, the trainee population is controllable through funding mechanisms.

Turning off or turning down the PhD tap probably hurts new investigators the most, because they would have a harder time recruiting postdocs/RAs. However, by limiting how many trainees the BSDs are allowed to burn through and discard to get their next Cell paper, this may even out the distribution of trainees and ameliorate this a bit.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 10:54 am

agreed and agreed miko. excellent solutions to Potnia’s point about breaking the Tragedy of the Commons cycle.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 10:55 am

” The system is taking longer to launch young biologists.”

NIH is so glued to this metric that they don’t seem to recognize it as a symptom, not the disease.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 10:56 am

I think NIH should stop the subsidy that encourages university programs to grow beyond sustainability and require NIH support to grad students be through training grants and individual fellowships (which would allow NIH to control directly the number of NIH-supported PhD students). This means, no grad student research assistants on PI grants.

But the other thing that needs to be done is to demand that institutions support their faculty and require that PI’s be supported by some percent off of non-federal funds. My off the cuff number would be 25% non-federal fund supported.

Why do we need the second criterion as well? Because the tightening of the US-produced PhD would not change the overall structure producing an oversupply of PIs depending on NIH grants. Getting rid of the US spigot would just mean foreign-trained PhDs, coming as post-docs, and then aiming for grant-initiated faculty positions.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 10:59 am

But, I think the underlying problem with all these arguments is who they are supposed to help. Would this change the quality of the science done in the US, and if so would it be for the worse? If so, we’re asking society in general to give up significant rewards in return for protecting graduate students from themselves (since no one is forced to go to graduate school)

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 11:00 am

demand that institutions support their faculty and require that PI’s be supported by some percent off of non-federal funds. My off the cuff number would be 25% non-federal fund supported.

1) Where is this money to come from?

2) Why should the NIH get its work done for cut rate in this way and what proportion of other Federal services/contracts work in a similar way?

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 11:08 am

“1) Where is this money to come from?”

Institutions with strong enough endowments support through their operating funds. Charitable foundations.

And, people get fired, and the number of PIs go down, and there’s less incentive for universities to hire “free” professors who contribute to the overall oversupply problem.

“2) Why should the NIH get its work done for cut rate in this way and what proportion of other Federal services/contracts work in a similar way?”

I figure that about 25% of PIs time is spent in the grant writing game, and that you are not allowed to be paid on federal funds while lobbying for federal funds. Of course, I’m making up the number, but it’s not 0%. Other contractors presumably solve that problem some how (with reinvested profits? other contracts?)

What does the “overpopulation” graph look like if one looks at the trend towards soft-money positions? My guess is that a significant part of the expansion of the PI population is the result of soft money positions, and the continuing incentive to universities to expand while placing the risk on individuals (PhDs, PI’s)

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 11:10 am

Miko – exactly right.

The NIH minority supplements work in this way – you get one per R01. You have to apply & justify. They sometimes get turned down. Let everyone get one student per R01. I am also not opposed to the idea of limiting Post-doc level trainees too. I see huge amounts of abuse of that level position.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 11:13 am

Knowing where the bubble is is important to not destroying the entire scientific education infrastructure of the country. So it means figuring out how to institute caps in a way that recognizes that the bubble is asymmetric, and then how to use existing scientists to replace the lost labor, because there is some demand for labor, though only through government supply of resources to feed that demand. Existing scientists will be as or more expensive than graduate students, and the issue about how asking them to freelance for the rest of their lives on project grants that are of shorter duration is also a problem. I don’t think there will be any solution without money, but even if there were an influx in money, the system should change, instead of the “expand demand to keep fighting over supply” situation we have now.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 11:13 am

Shut off the PhD tap (from 2nd and 3rd tier institutions).

At the very least, be transparent with students about the odds

of career success from a 2nd rate program.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 11:14 am

You wrote this as though getting an academic position is the *only* option for a Ph.D. The grad program at my school strongly encourages their students to prepare for a teaching job. I don’t have the numbers, but I know many students who have moved on to do a post-doc, and got teaching jobs within a reasonable time frame. Others go off into private biotech companies. I don’t understand why you see these other options as failures. In fact, I think it is a failure of the grad program whose students cannot diversify and only see a faculty position at MRU as the single end-point. It’s narrow-minded.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 11:20 am

Alternative careers are a failure in so far as there is a mismatch between grad students’ goals upon entry and their career outcome. I judge that at present there is a very large imbalance.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 11:27 am

“Alternative careers are a failure in so far as there is a mismatch between grad students’ goals upon entry and their career outcome. I judge that at present there is a very large imbalance.”

Although I agree with the overall conclusion (i.e. alternative careers are not a valid answer to the over-population problem), I do not agree that the mismatch used to judge should be “goals upon entry” and “career outcome”. There’s nothing wrong with someone changing their mind during their graduate degree, and people really do. And, I’d guess there’s some field specificity, even within biology, of the viable non-academic options.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 11:48 am

Foobar – you are clearly at a BSD university. There are lots of good folks who are at those 2nd tier places, who do good work, and find their students jobs, and manage small laboratories. Rather than judge an institution by the size of its dick, why not access the mentors?

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 11:48 am

You don’t need a PhD for the majority of these bullshit “alt careers”. The requirement for a PhD is simply a reflection of the applicant pool – i.e. disgruntled post-docs who can’t find any kind of faculty appointment.

To me, DMs point is a no brainer. But I wonder if the market will ever take care of itself. You do wonder why kids are still interested after they see their dismal prospects laid out in front of them. Perhaps they don’t see the data, perhaps they just think they will be the exception, or perhaps they are just willing to gamble to do something they love. Either way, if I were in their position today I wouldn’t do anything differently and I would for sure roll the dice.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 11:49 am

Shut off the PhD tap (from 2nd and 3rd tier institutions).

At the very least, be transparent with students about the odds

of career success from a 2nd rate program.

Really? And I assume you have data on this?

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 11:59 am

DM, what about your idea (or maybe it was someone else’s in the Twittersphere) to enforce a retirement age, too? I know of multiple 70-something year-olds who are still running large labs (postdoc farms, really – not many techs or grad students) and a few of whom are so old, they no longer care about their training track record, so trainees just sort of languish in their labs, cranking out data for grants and waiting patiently for high impact papers to get published…. Yet, those older PIs continue to get NIH and other funding, and that’s what allows them to persist.

Enforcing a retirement age would help to free up some jobs. The NIH could help in this regard by automatically disqualifying PI’s over the age of 70. If they don’t want to retire, I’m sure biotech would love to have their expertise. And, call me a socialist if you want, but if they aren’t retiring because they aren’t satisfied with their pensions, then perhaps they should fight for better pensions instead of writing grants.

I also agree with Potnia Theron’s suggestion to limit the number of postdocs, as well.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 12:05 pm

As of right now, BSD universities are doing everything they can to support as many biomed graduate students as possible.

If the goal is for NIH to shift as much of the fiscal burden of supporting biomedical research onto institutions as possible, then the the more students and post-docs and PIs supported by training grants, fellowships, and career awards instead of RPGs, the better. This is because fellowships, training grants, and career awards only allow 8% indirect costs, instead of whatever the institution’s negotiated rate is for RPGs. In fact, much to my surprise, even the substantial direct costs on career awards beyond just salary support for the awardee are also subject to this 8% limit.

So paying the salary of a PI on a K01 or a post-doc/grad-student on a T32 or individual NRSA costs the NIH a fuckeloade less than if they are supported by an R01 or other RPG. The balance of costs is borne by the awardee institution.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 12:05 pm

“If they weren’t good value, you’d switch over.”

I largely have done so.

At this point I train grad students because it’s good to have bright-eyed-bushy-tailed noobs in the lab. They’re willing to try the sorts of stupid things that more experienced (jaded) postdocs might not try.

What were you saying, again?

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 12:09 pm

Bullseye.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 12:09 pm

Lady Day, that’s probably illegal on the basis of age discrimination (which prohibits disadvantaging the old but allows them to eat the young, who apparently can’t be disadvantaged due to age). This is part of the bigger Boomers Are Terrified Of Death And Will Nom Everything problem.

But it is also abetted by everyone… being in a BSD lab is perceived as an advantage by a lot of postdocs, even if the BSD did their only work that matters 25 years ago. This is because perceived prestige lets the oldz still publish well and still do a lot to get jobs for the PDs whose countenances pleaseth them. So, study sections have to stop giving them grants, and search committees have to stop giving a shit that someone is from their lab. They’ll get the message.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 12:13 pm

>At the very least, be transparent with students about the odds

>of career success from a 2nd rate program.

> Really? And I assume you have data on this?

Check out Miko’s blog post on “What matters for the short list”

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 12:16 pm

When I started grad school at the bottom of the last funding trough there was similar doom-and-gloom and I assumed that I’d be taking an “alternative” career path upon completion of a PhD or postdoc. And there weren’t even any fuckin’ blogs full of whiny comments back then (unless you count USENET newsgroups). Still amazes me that the young ‘uns sign up for grad school and don’t bother to look at career outcomes, read the blogs & comments, look at the news sections of Science or Nature or The Scientist.

Someone is offering you a “free” graduate degree; but as young adults you should be mature enough to consider that there is almost never a free lunch. Caveat fuckin’ emptor, prospies.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 12:16 pm

Not in favor of mandatory retirement at all. My division chief just hit 70 and I’m not sure he has even hit his peak yet. Absolutely cannot tarnish all the old boys with one brush.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 12:35 pm

Shutting off the tap will take 10 years to have any impact. All those trainees currently in grad school or post-docs still have to wind their way thru’ the pipe. How about instead, we impose mandatory retirement on the age 65+ borderline emeritus academics, to open up more positions? Many of these folks have been hanging on for a few extra years, to try and claw back some of their retirement account losses incurred in the 08-09 crash. Time to put ’em out to pasture and bring in some new blood.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 12:52 pm

How about paying graduate students more? 🙂

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 12:52 pm

@Ola

…you mean those R01 XY01234–35 entries that one stumbles across in NIH Reporter?

FWIW one can also without much effort retrieve >350 examples of investigators pulling >$1M in direct costs per year off of single RO1 grants.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 12:57 pm

Dear Everyone who wants mandatory retirement or alternatively to shoot the Olde Farts:

1. It is against the law.

2. Not everyone over 40 /50/60/70 is useless, taking up space and padding their TIAA account. Some of them are actually working to support/help/mentor younger people.

3. You do NOT want oldies working on lobbying for higher pensions. That is one of the country’s big problems right now.

4. The boomers are not eating everything in sight. In fact, they probably had a hand in training you. Everyone who is young is not an oppressed angel who would cure cancer if only given a couple of really good grants.

5. As oldies retire, universities, often as not, do not replace them with TT positions.

6. There are Evil Vile BSD’s in every age group. Your definition of Evil and Vile may not be someone else’s.

7. Arbitrary criteria that are divorced from quality and productivity hurt everyone. This has been proved empirically by many economists.

8. Some people actually like working and are doing a good job. Who the fuck are you to decide that after X years old they are not?

Sincerely,

Potty

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 1:01 pm

How are low-cost graduate students any different than low-cost postdocs? In my experience, postdocs tend to be able to hit the ground running a little faster, but in practice, a well-trained (4th year in lab, peak productivity) graduate student and a well-trained (2nd year in lab, peak productivity) postdoc are about equivalent. (While it is true that I’m comparing 4th yr GS to 2nd yr PD, the first year GS isn’t in my lab, and the variance is so large, that I wouldn’t want to go only PD – I’d rather look for the best person.)

I think the real issue is not the oversupply of graduate students, but that we need to find another option to do the non-PI part of the science. But I don’t see why all the hatin’ on graduate students? The real problem is that we are using “training” as a way of getting low-cost productivity. It’s an old-school apprenticeship model and works well only as long as the apprentices get to be masters some day.

On the other hand, I don’t think you are being fair to the alternative careers. I know LOTS of people who went into alternative careers, where they didn’t NEED a PhD, but they think it helped them. (Who am I to judge their reasoning?) There are also lots of careers where one does need a PhD (certain kinds of industrial and defense research) which get counted as “alternative” careers. I do think each of us has to look at our production of graduate students and ask whether we’ve done good by them. (I know when I look at my students, I’m very proud of where they ended up and I know that they are using the training I gave them.)

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 1:02 pm

“7. Arbitrary criteria that are divorced from quality and productivity hurt everyone. ”

Like age?

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 1:08 pm

Clearly, older investigators are getting better and better, and younger investigators are getting worse and worse. The increasing age at which investigators get their first R0-1 equivalent, and the increasing median age of NIH-funded investigators, proves this to be so.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 1:09 pm

I think it’s a wonderful idea for American universities to cut way back on the number of graduate students.

Most of us in other countries (e.g. Canada) will be more than happy to pick up the slack. It means that Canadian graduate students will have a much better chance of competing for the best postdoc positions in the USA. So will Chinese and Indian graduate students.

What’s that? Oh, you forgot that other countries exist and that science is international?

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 1:12 pm

” But I don’t see why all the hatin’ on graduate students? ‘

It’s not. Fewer PhDs means fewer PDs mean fewer people vying for the TT jobs that might exist (or not) in the future. No one is saying suddenly get rid of a bunch of current PhD students.

I was snarky above, but I am not in favor of mandatory retirement (though I do think it’s rank hypocrisy that age discrimination only applies if your’e old — let’s look at the any numbers on relative advantage of boomers and Gen Y). I am in favor of grants and papers being judged on their merits rather than who can throw their weight around (who isn’t, right?), and I am in favor on serious limits on how many trainees and grants you can administer as a PI. The BSD culture is the problem, not age, it just often correlates for obvious reasons.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 1:17 pm

Larry, everyone knows The Canada Effect is well within rounding error in everything except syrup and softwood lumber. China, Korea and India…

Preventing spending research grants on trainees would mean immediate curtailment of foreign PhDs/postdocs in US institutions as most NIH mechanisms are not available to them. I think this is very bad, and there would have to be mechanisms to ensure opportunities. I would suggest that there be no nationality restriction on training grants and that they come with a green card. We’re good at assimilation.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 1:20 pm

Fine, Portnia Theron, let the old farts hang around as Emeriti. They get an office and can continue to influence people, just not directly. They can spend their time reviewing papers for journals, perusing the literature, catching errors in papers, and writing cranky comments and rebuttals to journals.

Also, the problem is not with higher pensions, but the way that funds are allocated.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 1:20 pm

Oh, and thank you, miko.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 1:23 pm

As Emeriti, old farts can still continue heckling grad students, postdocs, and junior faculty at seminars, too. And, if they want, they can continue on with mentoring – providing junior faculty with sage career and grant advice. There’s still a lot they can do without sucking up NIH funding.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 1:30 pm

If you want to reduce the number of mouths at the trough, you have to reduce the number of PIs, not the number of grad students. Reducing the number of grad students doesn’t translate into fewer PIs, even in ten years, unless you do it so severely that there are not enough people to fill the available PI slots. And, as pointed out, there will still be competition from foreign PhDs, so gutting American PhD programs would have no effect on success rates.

People starting their PhDs are adults, they can decide for themselves if it’s worth it.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 1:35 pm

You can also reduce how much each mouth gets. Which fits well with reducing the number of trainees being supported, which provides cost reductions in salaries and in research expenditures.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 1:37 pm

I don’t know where this notion that ALL (or even most) old investigators are messing around smoking cigars in their offices collecting NIH money for doing nothing and failing to mentor the youngsters comes from. You are kidding yourself if you think this is the problem or that forcing retirement will all of a sudden lead to an increase in TT jobs and 30% success rates at the NIH. Not. Going. To. Happen.

Lady Day – I don’t know where you are located, but some of our 70+ investigators are staggeringly good. Science would genuinely suffer if we lost them.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 1:46 pm

I see bob’s point.

It’s basic ecosystems biology – you have to have some turnover. The academic ecosystem suffers when there are too many young trainees coming in and too many old dudes sitting around in their offices all day, churning out grants because they will do *anything* to avoid spending all day at home with their wives (every single 70+ year-old that I know is male and white, incidentally).

That said, I have heard that grad students increasingly join biomed programs with their eyes on alternative careers or industry jobs.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 2:00 pm

Science is suffering from losing the 2-3 young people that can’t get in the door (and start their 30-40 yr careers) because of the one 70+ yr old (salary-wise). Not to mention that said brilliance may or may not depend on the near-PI level efforts of multiple senior people in said geezer’s lab.

NIH POs make decisions about “their investment” all the time. Most usually to the detriment of the young. They extend the exception pay pickups to the established- how is this not age discrimination? and if they decide to stop extending their pickups to someone 68+ and hand them to a 38 yr old…who is to prove it is age discrimination?

I’m pleased that we are already rousing the strong supporters of the anecdote that proves how we cannot put down policy that affectgs a particular category of investigator. I’m sure you are all smart enough to realize that every. single. category. of investigator has similar brilliant exceptions. yes, even in Podunk U Department of Skunkherding.

I think we simply cannot get serious until and unless we are willing to say that saving Professor Anecdote isn’t worth the DoNothing pain of using him to avoid a bold policy.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 2:08 pm

@DM “Science is suffering from losing the 2-3 young people that can’t get in the door (and start their 30-40 yr careers) because of the one 70+ yr old (salary-wise). ”

Really? Evidence of this? Why is it assumed that adding 2-3 more juniors, who weren’t good enough to rise to the tippy top on their own, is better than the half-a-day old dude?

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 2:12 pm

At my recent campus visit I met with a group of students, only two of whom were planning to do a postdoc. I felt this was good/sad.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 3:00 pm

dr_mho:

well, since the evidence currently being proffered in support of Dr. OldBeardedOne is purely anecdotal….the people I refer to are ones that I know. People in my field*, promising postdocs who can’t get jobs and junior faculty who are struggling to land grants. On the other side, I also know the >65 crowd in my field and how many NIH grants they have (RePORTER) and their productivity (PubMed).

On the salary end I’m making assumptions based on what junior folks are getting paid these days (in my institution and for anyone elsewhere that I happen to know, public Uni published salaries) versus senior folks (public Uni published, and other sources; also the NIH cap).

*and the occasional anecdote from people that I know personally that don’t happen to be in my field.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 3:04 pm

@dr_mho: We know this because there is a large body of literature on when people in different fields tend to do their most important work. Even in biology, the key work is seldom done much after age 50. Look at the work that gets people into the NAS or wins Lasker prizes, etc.

By constricting the number of investigators in their 30s and 40s who have the resources and intellectual freedom to pursue what THEY see as the most important and interesting problems, you are killing the enterprise.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 3:21 pm

“People starting their PhDs are adults, they can decide for themselves if it’s worth it.”

“Still amazes me that the young ‘uns sign up for grad school and don’t bother to look at career outcomes, read the blogs & comments, look at the news sections of Science or Nature or The Scientist.

Someone is offering you a “free” graduate degree; but as young adults you should be mature enough to consider that there is almost never a free lunch. Caveat fuckin’ emptor, prospies.”

As a 26-year old PhD student I would emphatically like to state that I am NOT an adult, nor do I expect to be one anytime soon. I’m only barely more mature than I was when I entered my PhD program as a 22-year old. I only knew like five names of scientists in my field – much less did I have any idea what the state of academia was like in anything other than the vaguest of senses.

I slid into a PhD program because I thought “hey science is cool and I kinda like it” and because I didn’t have a clue what else to do.

So in other words – I didn’t do my homework. So why shouldn’t I and others like me be taken advantage of? If we were dumb enough to get in this game in the first place without really knowing what we’d get out of it, why not exploit us?

I know I won’t be a research PI – not just because there’s no chance I’d get a job, but because I don’t want to move all over the country and I don’t like the science enough to deal with the BS required to obtain funding (although perhaps I would like it more if I thought there was a future in it!). So while I’m here, the system might as well get out of me what it can (unfortunately for the system, I’ve as yet been spectacularly unproductive, so hah!).

If you want to really reduce the number of people applying for funding, you need to reduce the number of people applying for funding: the PIs themselves. If you reduce PhD students then you reduce postdocs and then who does the work for all these young PIs seeking funding anyway?

The only solution to have more careers for young scientists is for society to invest more money in science. Since the system is saturated now, it’s all just a zero-sum game.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 4:10 pm

That’s exactly what I did. What I did not do was assume that “sliding into a PhD program” because “hey science is cool and I kinda like it” is equivalent to entering a career track.

Taken advantage of? I got PAID by TAX DOLLARS to do bench science for five years, made discoveries that are still heavily cited a dozen years later, and emerged with a Ph.D…

…and, surprisingly, a career as well. But to be honest, I didn’t take the “career” part seriously until I had renewed an RO-1.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 4:30 pm

Perhaps the tap should also close from the other end. My boss and several members of our faculty are well over 65 and not only fully supported by NIH but have large labs which also are fully supported. How are young investigators supposed to compete with people who have 25, 30, 35 and more than 40 years of experience?

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 4:33 pm

oh I can’t disagree… I’ve never assumed that this was a guaranteed career track. Nor can I claim that I’m not being paid – I get paid really well compared to most PhDs (and way more than I should given that I am not and probably won’t produce anything like the heavily-cited discoveries you’ve made). By “taking advantage” I’m referring to the fact that grad programs advertise and attract students by selling the academic route, and the culture sort of reinforces this. I’m not talking about the pay – after all, I could have slid into something else and probably gotten a comparable salary by now (though I can’t prove that of course…).

Pay isn’t what motivates people to enter PhD programs – it’s a sense that science is cool and that being a professor is kinda prestigious. I can’t name anyone in my entering class who was coming into it because they wanted a PhD so they could go into industry. Everyone coming in (I was no exception) either openly wants to be in academia or they admit that they’re not sure where they’ll end up (which means they secretly hope they’ll end up in academia).

The issue I have with “shutting off the tap” is that PhD students and postdocs do most of the work in science. They are the biggest slice of the labor pie. Gutting that labor force might over time reduce the pressure on those postdocs and young PIs seeking R01s, but then who do they have to do the work they get funded for? Or is the goal that every PI has only one grad student and one postdoc?

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 4:36 pm

“How are young investigators supposed to compete with people who have 25, 30, 35 and more than 40 years of experience?”

By having had an original thought in the last 20, instead of living in a fawning postdoc echo chamber of self-regard?

#notallofthem

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 4:37 pm

who do they have to do the work they get funded for?

Part and parcel of my consideration is that the exploitation of labor that is being practiced by the NIH extramural research system is unconscionable.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 4:56 pm

Considering my boss has a stated preference for new grad post docs over technicians with experience, I cannot disagree with your assessment of exploitation of labor. However, I cannot lay the blame solely with the NIH. It is a self perpetuating cycle. Post-docs are more easily disposed of if they don’t work out than technicians who are staff members.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 4:59 pm

On the one hand I really do think that young people should think a bit more critically before they commit 5 or more years to a graduate program.

That they don’t is a symptom of the infantilized state in which too many students emerge from high school and college; itself due to the overly protective and regimented modes of child rearing that currently predominate.

In a real sense, by the time we get ’em, it’s too late.

On the other hand, there’s no question whatsoever that if we view grad and postdoctoral training programs as workforces doing research that the NIH is contracting, rather than “free school,” there is a labor exploitation problem.

The solutions to both problems are necessarily largely identical. Incentives to take too many students need to be reigned in (see CPP’s comments). And there need to be mechanisms that allow some reasonable fraction of the most productive and creative trainees to have a reasonable and stable career path that grants them the freedom to do unexpected breakthrough work or, failing that, really solid science.

@mbeisen’s ideas may not be the right ones but they certainly point toward the confrontations with reality that have got to occur if we’re not to abandon an entire generation of young scientists.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 5:16 pm

This was treated in an article in BioScience about 1980. I do not have the resources to find a copy. The argument was that science in general, and biology in particular, had followed a logistic growth curve, with rapid growth over a period of several doublings in amount of money spent on science. They projected that there would never be another doubling; that science was at carrying capacity. That means 0 growth and fierce competition for existing resources. Some old areas of science will diminish, and new areas grow at their expense. They suggested that the number of large labs would shrink, and thought that there should be no more than one PhD program per state, and that would be too many. The number of PhD jobs is independent, to a large extent, of the number of PhDs produced. And here we are today.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 5:35 pm

I don’t know if this was mentioned in the extensive discussion above, but some schools are turning down the tap. Our institution reduced admissions by close to 30%. The program directors got together and decided that three students per program per year was necessary maintain a viable graduate program. All grad programs recognize the Ph.D. problem, but from a slightly different perspective: we have to place all of these students into funded labs. That is becoming a serious challenge.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 5:55 pm

I’m very capable in the lab and love bench work, so I could handle life without a grad student. Some PIs forget they can do bench work as well, and if data needs to be generated, then get it done. If reducing the number of grad students increases the chances of getting funded, I will happily trade my hours writing grants with data generation. I would miss training grad students however. Plus grad students will not leave you for medical school after you have spent six months training them. Don’t shut off the tap, just turn it down drastically.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 6:21 pm

@spiny norman To add to your “other hand” analysis:

Is there any way we can consider grad school “free school”? If that’s the case, then it should be training us for what we’re going to be doing – and it plainly isn’t. We’re being trained to be academics, not consultants, industry techs, teachers, or writers. If that’s how grad school operated, then maybe there’s no complaining. But otherwise we have to see it for what it is: the bulk of the scientific labor force.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 7:37 pm

@jipkin:

I don’t agree that education is necessarily vocational training. If that’s what you’re after, go to med school, apprentice as a plumber, train as medical technician, become an Oracle-certified database administrator, or enter ROTC.

If you go after a Ph.D., look closely at your career prospects and think closely about your motives. I cannot think of a single field — including engineering — where a Ph.D. provides any guarantee of future employment within the field.

If biomedical research is your thing and you value job security more highly than I did (I was not married and did not have kids when I started), I strongly recommend getting an M.D. from a good school, doing research as you can manage it throughout your training, and following that with a postdoctoral research fellowship in a really good basic science lab. There are really good ones targeted at M.D.’s. Don’t bother with the M.D.-Ph.D. — a waste of time for most. Do one or two research fellowships and then find yourself a good job at a med school.

If I had it to do again, that’s exactly what I would have done.

Worked out nicely for Brian Kobilka…

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 7:46 pm

Finally got there. Welcome. The next thing you need to do is look at where all the graduate students are trained. Hint: You could solve the problem across every field by closing the University of California.

The fact is that the top quarter of places trains over half the PhDs, the bottom quarter, almost none.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 8:51 pm

Oooohooooo, ER. Got any links? This sounds good….

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 8:51 pm

“You could solve the problem across every field by closing the University of California.”

They’re trying! They’re trying!

Just wait.

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 8:53 pm

Dang, ER.

I’m going to have to abandon my advocacy for the Univ of the USA, aren’t I?

LikeLike

January 28, 2013 at 11:41 pm

I’ve just written about this whole pyramid problem about a week ago. It boils down to the fact that it’s in nobody’s interest to disenchant young PhD candidates about their future career prospects. In fact Universities, PIs and the NIH have every incentive to encourage people to get into those PhD programs.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 12:10 am

“It’s in nobody’s interest to disenchant young PhD candidates ”

I try. FSM knows, I try…

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 3:36 am

I try to disenchant the PhD students that doing a post-doc will be the magical ticket to happiness. Get your degree, find where having a PhD adds value (is special and/or unusual) and go there as soon as you can (hint: since all post-docs have PhD’s the value of having a PhD among post-docs is zero).

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 5:17 am

Special or unusual….barista?

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 5:54 am

Physioprof’s point that This is because fellowships, training grants, and career awards only allow 8% indirect costs, instead of whatever the institution’s negotiated rate is for RPGs.

is kinda huge, because it means that shifting the balance to fellowships etc has the doubly happy effect of reducing the “factory-lab” as well as cutting into the overheads that produce, in the immortal words of miko, those grasping “spindly little deanlet arms.”

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 6:18 am

Among the advantages of having graduate students and postdocs be your scientific “labor” (vs. technicians) are the considerable passion and creativity they bring to science. I think the only way to replace them will be with decent paying, stable jobs for Ph.D. scientists. After all, there are plenty of people with the dedication and intellect to be professors who don’t want to spend their days writing grants and managing people. This would also ease some of the “pain”; hire the people that have already been trained and simultaneously stop taking so many (*&^ grad students.

But how do we do it? NIH grants are for 2-5 years. Institutions aren’t even willing to guarantee professor pay. Will anyone go to grad school for a career changing jobs every 5 years?

Maybe NIH needs to reward university administrators for long-term faculty/staff support instead of edifice complexes.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 7:03 am

If we carry on like this Nature is going to write another editorial about how we are all wasting our time blogging and not lobbying!!!

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 7:17 am

ER might be referring to the “Survey of Earned Doctorates” data.

According to the SED data, there were over 8,000 doctorates

awarded in “Biological Sciences” alone in 2010.

That is a huge oversupply because there is at most a couple

of hundred tenure-track openings per year.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 7:19 am

“Maybe NIH needs to reward university administrators for long-term faculty/staff support instead of edifice complexes.”

Again, part of lobbying has to be to show NIH or others why it would be in their interests to undermine the pyramid scheme. The answer might be that there isn’t any interest, unless students abandon the profession. And, even that won’t be enough if it’s only Americans who abandon the labs, which can still be freely filled from international sources.

The model persists because it produces a lot of science. It won’t burst unless everyone abandons it, or we can show that it doesn’t produce “good” science. I’m not very hopeful that people through out the world will abandon the field (it still is a good option for many and for others its a dream). I’m worrying about the second (that resource limits produce bad science), but I’d be hard-pressed to prove it.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 7:20 am

NPG does not have the same interests that we do. Ignore them. They like the system that exists juuuuust fine. Their only play is “more”. Cutthroat competition of scads of postdocs suits their approach to a tee.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 8:51 am

What would be the incentive for not training grad students? As a commenter noted above, they are hard-working, bright, hungry, somewhat cheap, and produce novel ideas. Without monetary incentives, only schmucks and PIs who care about the well-being of the students will take fewer students. That won’t be enough people/institutions to make a difference.

My colleagues in England have PhD students that pay tuition and are not paid stipends, like MS students are treated here. Brits please correct me if I am getting this wrong. The students are all foreign. Is that where we are headed?

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 8:54 am

It is a brilliant suggestion but Universities are going to fight it. If it is carrot only (expansion of nrsa), they will stop permitting many apps

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 9:43 am

Part of the problem in Science is that the technical track and the managerial track are the same track. Particularly in Bioscience, the Masters degree is under utilized by the discipline as a career trajectory. Engineering and several other fields have masters/certification structures that provide a workforce that is separate from the managerial/conceptual leadership. Also, the fact that you cannot get a job with a B.S. in biological sciences says volumes about the way our profession handles undergraduate preparation.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 10:48 am

http://chemjobber.blogspot.ca/2012/11/acs-webinar-on-doctoral-glut-be-glad.html

Back in November, Chemjobber showed a graph of the number of PhDs and MDs awarded annually over the past few decades. The increase in the biomedical field for PhDs is staggering.

Where do we expect these graduates to go after the PhD? Where are the jobs? Why are we training so many of them?

As shown in phdcomics: “beware the profzi scheme”

http://www.phdcomics.com/comics.php?f=1144

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 11:12 am

thanks. i’m updating the post, this is so good. what a tale it tells.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 11:54 am

This discussion was picked up by Megan McArdle:

http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/01/29/too-many-stem-students.html

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 12:33 pm

Yes, We’ve run all out of science. Let’s not train anyone to do it anymore, and outsource innovation overseas. Or, settle for the innovation that undergraduate and Masters level students can muster. Will it be enough for a competitive economy? I guess we’ll see.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 12:37 pm

So, I was semi-serious about paying grad students more. What if we unionised? At the moment, we’re being exploited (sure, it’s not exactly stitching trainers for $1 a day, but we’re giving more value than we’re getting. Mostly). The most immediate effect would be a decrease in the number of graduate students, because PIs couldn’t afford us any more.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 12:43 pm

Remember when the physicists went through this lament? I know the first step was that they got sucked up in the quant world. What was the next step? Did the number of physics PhDs actually decrease? Or did physics PhDs become a path to the alternative career of quants?

And, are we talking about STEM, or biology/biomed?

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 1:00 pm

Dear Ghod, not McArdle.

In fairness her article is only slightly unhinged, towards the end. But please let’s not have the conversation split and continue over there, Where the Stupid Things Are.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 1:03 pm

“Particularly in Bioscience, the Masters degree is under utilized by the discipline as a career trajectory.”

Suuuuure. And if you have a lot of students mastering out, one guess what’s going to happen when your program’s T grants come up for evaluation and competitive renewal.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 1:05 pm

Oh hell. McArdle is one of the stupidest humans on the entire planet. Among journos, only Gregg Easterbrook is more of a drooling imbecile.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 1:09 pm

Really? I don’t know this person…? Reasons?

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 1:47 pm

McArdle should be appealing to us scientists as she typically employs rational approaches to economic and political questions. You may certainly not agree with her conclusions – sometimes she does stretch to make a clear conclusion – but her analysis is usually interesting and thought provoking. I find her to be a very useful read for my thinking.

Her take on the discussion here is pretty spot on, I think.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 1:52 pm

Here’s McAddled’s latest plumbing of the depths of human stupidity: http://wonkette.com/493462/megan-mcardle-proposes-the-worst-solution-to-anything-ever

and here’s an earlier one: http://junkscience.com/2012/02/28/megan-mcardle-too-stupid-to-opine-on-global-warming/

If you need any more, just google something like “mcardle stupid”.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 2:31 pm

@Joe: The only PhD students who pay full tuition (bench fees) in the UK are non-EU/non-UK citizens who can afford it. Given the money involved, it is is rare to see these students in good departments where almost all students are on full rides. I can think of only one self-pay student during my PhD studies in the UK. It is more common to find them in MSc or MRes courses.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 2:35 pm

Oh hell. McArdle is one of the stupidest humans on the entire planet. Among journos, only Gregg Easterbrook is more of a drooling imbecile.

Ha! Are you CPP in disguise?

Spiny, did you check out that figure that respisci posted? We could have done with that in one of our previous debates.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 5:40 pm

DM

Easiest place to see this is the 1995 Research Doctorate Programs in the United States where they ranked each field by ordinal position

Continuity and Change

http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=4915

The more recent data has to be teased out of a humongous Excel spreadsheet

https://download.nap.edu/rdp/index.html??record_id=12850 without any singlequality parameter.

Results for Chemistry (Using Research Productivity as the metric to sort against PhD production)

Top Quartile 49%

Second Quartile 27%

Third Quartile 15%

Fourth Quartile 9%

OK, only 49% in the top quartile in chemistry mea maxima

UC was 6%

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 5:42 pm

The other thing to note about the UK is the PhD student support is only for three years, and then you are graduated or poor.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 7:04 pm

Wow… McMegan and thought provoking, that’s a real stretch. I usually go to projectile vomit, but that’s me. If McMegan wanders onto something intelligent, it was the proverbial blind squirrel finding the nut. That is not to say she isn’t manipulative and able to convince the naive that she has somehow thought something through; that she is quite good at doing.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 7:53 pm

What if we paid grad students LESS? Like, A LOT less. This is in addition to limiting the amount that can be paid from grants, paying more of them from competitive fellowships with low overhead, and some other good suggestions upthread.

Fewer students would be compelled to go to grad school because it’s easier than getting a real job, or is the path of least resistance. We get paid pretty well, considering we’re getting an education. I know SO many grad students who started because of these and other terribly misguided reasons, rather than any real desire to do science. Many of them will self-select out of starting grad school in the first place. They’d also be more motivated to finish quickly and to not languish while raking in $30K/yr.

Pay good post-docs better, limit their terms, and use most of the extra money freed up from half-assed trainees for hiring professional staff scientists, who can run circles around a 2nd year grad student, even working half the hours.

Fewer students apply, more drop out because they actually suck, and the good ones stay motivated to finish faster. They could then try for the academic post-doc/PI track, or go for staff scientist jobs (since there will be a demand for all the labor that the PhD students used to do) or “alt” careers. I say this as a soon-to-defend PhD student, by the way. I would happily accept dramatically reduced pay if it means my career plans as a staff scientist will have a chance pan out.

LikeLike

January 29, 2013 at 9:24 pm

McArdle for dummies*, exhibit A.

*Department of redundancy department.

LikeLike

January 30, 2013 at 9:27 am

The problem with paying grad students less is that you select for their parent’s income or increase the loan burden beyond repayment possibilities.

LikeLike

January 30, 2013 at 9:29 am

Spiny, that made my day.

Admittedly it’s only 10:30 am and I’ve given up coffee, so it’s a low bar. But still, yer a funny guy for a giant imaginary hedgehog.

LikeLike

January 30, 2013 at 7:46 pm

jipkin,

FWIW, one suggestion I’ve floated in the past on my blog is for students to first do a year working before starting a PhD. Financially students would be better off. Some places might even offer working year+PhD+return deals. Etc. One reason I suggested this is that some would realise they’d be happier not starting a PhD once they’d spent time in the workforce and fewer might just “drift” onto a PhD.

(If it matters, I did a year working, then choose to do a PhD.)

LikeLike

January 30, 2013 at 9:41 pm

Sorry, didn’t bother check what I wrote at the time I posted it: ‘choose’ -> ‘chose’.

LikeLike

January 30, 2013 at 9:47 pm

respisci,

Interesting graph, that. If you put the graph you link to and the ones on my blog (see below) together, and assume that a similar rise in PhD numbers occurs outside of the USA, it’s difficult not to pause for thought:

http://sciblogs.co.nz/code-for-life/2013/01/29/from-science-phd-to-careers-outside-academia-what-might-help/

I might add an update to my post…

(Does anyone know of a graph for the USA like those for the UK and New Zealand on my blog?)

LikeLike

February 1, 2013 at 6:39 am

[…] Fixing NIH science funding: First, a vexed conversation, then a righteous rant, then some specific proposals. […]

LikeLike

February 1, 2013 at 10:12 am

Dave asked: “Ha! Are you CPP in disguise?”

Hell no. I don’t even like fucking risotto.

LikeLike

February 1, 2013 at 11:17 am

Hmm, never tried that. It’s good to eat though.

LikeLike

February 1, 2013 at 11:58 pm

I am 100% with Larry Moran’s comment from a few days ago. This is not a closed system. If the NIH funds less PhD’s then that does not necessarily limit the number of PhD’s available, because other countries likely wont follow suit. If the problem is too many PhD’s without jobs its better to shut it down at the demand level (preventing or limiting PI’s from having postdocs) rather than the supply level. FWIW I think that is also a terrible idea. It would be helpful to refine exactly why having too many PhD’s trained is a bad idea.

LikeLike

February 7, 2013 at 9:24 am

[…] Math VI: The system needs an overhaul for sure. From grad student training through to PI's (which one way or another seems to be in the works). But even if we got rid of all […]

LikeLike

February 9, 2013 at 2:48 pm

[…] even though you almost certainly won’t continue on in academia because there are no jobs and no grant money . So despite an uncertain future, graduate school can, maybe possibly, be a good investment of […]

LikeLike

February 18, 2013 at 10:58 pm

[…] even though you almost certainly won’t continue on in academia because there are no jobs and no grant money . So despite an uncertain future, graduate school can, maybe possibly, be a good investment of your […]

LikeLike

April 29, 2013 at 11:25 pm

Doesn’t this article leave out the “life as journey” aspect? Certainly, prospective PhD students and postdocs should be informed about career prospects and options, but why must science education necessarily lead to a career? A short-term period in scientific research can be viewed as rewarding in and of itself. Because some of us also emerge with a long-term career, that shouldn’t blind us to the glory of actually contributing to understanding nature and publishing a journal article. Very few occupations offer anything like this thrill. Many young people spend a few years exploring acting, painting, writing, despite knowing quite well that the likelihood of being able to support themselves in these fields is very low. Fortunately, our societies are affluent enough to permit such quests. Yes, scientific research is full of mundane and arduous tasks, but I bet that writers etc. also don’t find every moment fun.

LikeLike

April 30, 2013 at 4:53 am

If we make it abundantly clear to graduate students, fine. As in, they *understand*, not just “we warned them”.

LikeLike

May 5, 2013 at 12:39 am

Why not follow the Australian system?

The students get their own scholarships and seed grants. The PIs do not pay the stipend to the students. The PI’s grants may supplement the cost of lab consumables for the students. If the lab run out of money, the PI may allow to use the student’s seed grant to pay for the technician salary provided that the student is writing up his/her thesis. A student in my institute get a $600k grant, the PI used it for salaries for himself, a post-doc and a technician because the student was writing her thesis and no longer need to do experiment.

LikeLike

May 5, 2013 at 7:46 am

“A short-term period in scientific research can be viewed as rewarding in and of itself. ”

Not clear to me why taxpayers should pay for a temp who needs several years of paid training to conduct biomedical research rather than a professional scientist. That it might be a rewarding part of someone’s journey isn’t very compelling to me.

LikeLike

July 27, 2013 at 5:01 pm

[…] even though you almost certainly won’t continue on in academia because there are no jobs and no grant money . So despite an uncertain future, graduate school can, maybe possibly, be a good investment of your […]

LikeLike

July 27, 2013 at 10:17 pm

sure

LikeLike

September 6, 2013 at 3:43 am

[…] are also trainees on the R-series grants working under a funded big dog. This is a source of some controversy, because it makes grants expensive (to cover salary for postdocs, tuition for phd students) and it […]

LikeLike

October 18, 2014 at 12:27 pm

[…] been suggested many times is that we are producing too many PhDs. Some people claim that we should turn off the PhD tap, which would make life easier for all down the line. Since over 80% of PhDs end up working outside […]

LikeLike