Finding God in the Brain: That Psilocybin Study

January 7, 2008

Abel Pharmboy of Terra Sigillata has a recent post covering Sol Snyder’s NEJM commentary (currently free) on finding god in the brain, an overview of some neuroscience thinking on religiosity. Abel and Sol both touch on a 2006 study by Roland Griffiths and colleagues [available to all from the MAPS site here] which reported on a study of the “mystical-type” experiences of humans following a dose of psilocybin. I’ll try to expand a bit on this since it was a very interesting study in many ways. Even though this is a bit dated by now, I wasn’t blogging back then so I’ll give it a whack. It should be obvious where this touches on some of my own scientific interests.

Psilocybin, of course, is

“a naturally occurring tryptamine alkaloid with actions mediated primarily at serotonin 5-HT2A/C receptor sites, is the principal psychoactive component of a genus of mushrooms (Psilocybe) (Presti and Nichols 2004, Biochemistry and neuropharmacology of psilocybin mushrooms. In: Metzner R, Darling DC (eds) Teonanacatl. Four Trees, El Verano, CA, pp 89–108).“.

In this it shares the presumed primary pharmacological action with the so-called “classical” hallucinogens such as LSD and mescaline. MDMA, by the by, is not a “classical” hallucinogen despite being an indirect serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, hence 5-HT) agonist (by virtue of releasing and blocking reuptake of serotonin) with some direct 5-HT agonist properties. There are some similarities in subjective effects but MDMA is sufficiently unique as to get people creating new subjective classifications such as “empathogen”, “entactogen” and the like.

The Hopkins group to which Griffiths belongs is one of the best, perhaps even the best, at conducting high quality, well-controlled and interpretable studies in humans on the effects of drugs (both recreational and therapeutic) which have primary or substantial effects on brain and behavior. For that reason alone this is worth a read, particularly for those that may be skeptical of either psychological experimental methods or what may be viewed as druggie “science”. This type of attitude may also be why the paper was accompanied by an editorial and four commentaries including from Sol Snyder, former NIDA director Charles Schuster and a prior ONDCP-er Herb Kleber [MAPS links for Kleber, Schuster, Snyder, Nichols].

The key elements for this study were

- 30 adult volunteers without prior hallucinogen use that were “medically and psychiatrically healthy). All had some degree of religious affiliation.

- All 36 volunteers indicated at least intermittent participation in religious or spiritual activities such as religious services, prayer, meditation, church choir, or educational or discussion groups, with 56% (20 volunteers) reporting daily activities and an additional 39% (14 volunteers) reporting at least monthly activities.

- double-blind, cross-over design with two sessions conducted at 2-month interval. In human psychopharm studies, one often prefers a more “active” control condition than an inert capsule/tablet because effects are dramatic enough to immediately break the “blinding”. Meaning it would be obvious to subject and researcher whether they were getting a drug experience or not. So in this case, methylphenidate (aka, Ritalin, the ADHD medication) was the alternate dosing condition. There were two people monitoring the subjects during the drug sessions, these are relatively experienced individuals, familiar with human drug studies but blinded as to condition. They had an average 23% error rate in judging which drug had been administered and opined that multiple doses of psilocybin were employed (a fixed dose was used) which suggests blinding was as good as one might expect.

- a series of questionnaires regarding the drug experience were completed 7 hrs after dosing.

- to give a flavor for the “state of consciousness” and “mysticism” evaluations:

- This questionnaire is based on the classic descriptive work on mystical experiences and the psychology of religion by Stace (1960; Mysticism and philosophy. Lippincott, Philadelphia), and it provides scale scores for each of seven domains of mystical experiences: internal unity (pure awareness; a merging with ultimate reality); external unity (unity of all things; all things are alive; all is one); transcendence of time and space; ineffability and paradoxicality (claim of difficulty in describing the experience in words); sense of sacredness (awe); noetic quality (claim of intuitive knowledge of ultimate reality); and deeply felt positive mood (joy, peace, and love).

- The Mysticism Scale has been extensively studied, demonstrates cross-cultural generalizability, and is well regarded in the field of the psychology of religion (Hood et al. 2001, Quasi-experimental elicitation of the differential report of mystical experience among intrinsic indiscriminatively pro-religious types. J Sci Study Relig 29:164–172; Spilka et al. 2005, The psychology of religion: an empirical approach, 3rd edn. Guilford, New York) but has not previously been used to assess changes after a drug experience. A total score and three empirically derived factors are measured: interpretation (corresponding to three mystical dimensions described by Stace (1960): noetic quality, deeply felt positive mood, and sacredness); introvertive mysticism (corresponding to the Stace dimensions of internal unity, transcendence of time and space, and ineffability); and extrovertive mysticism (corresponding to the dimension of the unity of all things/all things are alive).

- two months after each session (i.e., before the second drug experience in the first case) subjects completed additional questionnaires focused on possible persisting effects.

- Three adult “community observers” designated in advance by the subject as having continual contact were interviewed about the subject 1 week and two months after each dosing.

- The structured interview consisted of asking the rater to rate the volunteer’s behavior and attitudes … The rated dimensions were: inner peace, patience, good-natured humor/playfulness, mental flexibility, optimism, anxiety, interpersonal perceptiveness and caring, negative expression of anger, compassion/social concern, expression of positive emotions (e.g., joy, love, appreciation), and self-confidence.

So what happened?

At 7 h after capsule administration, … The total score and all three empirically derived factors of the Mysticism Scale and all seven scales on States of Consciousness Questionnaire were significantly higher after psilocybin than after methylphenidate. Based on a priori criteria, 22 of the total group of 36 volunteers had a “complete” mystical experience after psilocybin (ten, nine, and three participants in the first, second, and third session, respectively) while only 4 of 36 did so after methylphenidate (two participants each in the first and second sessions).

And at 2 months?

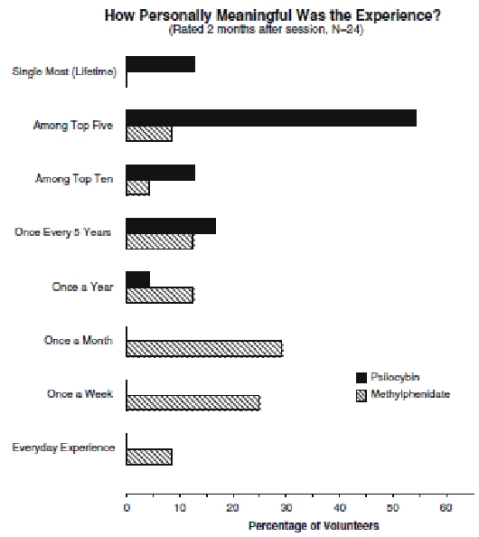

Figure 3 Percentage of volunteers who endorsed each of eight possible answers to the question “how personally meaningful was the experience?” on a questionnaire completed 2 months after the session (N=24)

The discussion gets a bit opaque for a number of reasons. The authors feel compelled to discuss the methodology and the context of prior (infamous) psychedelic research quite a bit for what should be obvious reasons. They soft pedal the implications for “mystical experience” quite a bit. It all boils down, however, to people having experiences quite consistent with other classical hallucinogens, that were rated as being “personally meaningful” two months later and that caused positive attitude, social and/or mood effects (by self report and with external verification).

Does this get us closer to a science of religion? Of understanding individual differences in religiosity? Perhaps. I certainly find it fascinating. It might give us a toehold on individual differences in, say 5-HT2A/C receptor expression or function, that pre-dispose one to religion. To plasticity in such systems that might result from religious experience. To understanding the mechanism that are involved in the more flamboyant behavioral expressions of religious ferver.

Finally, because I am very nearly unable to post on science without talking about funding. It is interesting that this research group, which has a very long history of very high quality research publication and NIH funding, put out a letter to drum up private philanthropy to support this work. (It would appear that psychedelic research philanthropy outfit, the Heffter Research Insitute, has provided some support to the Griffiths group.) One might deduce the reasons for this from the immediate response from the NIDA director, Nora Volkow, M.D., which speaks volumes. NIDA isn’t interested in anything that might encourage people to use recreational drugs. Period. But this seems short sighted to me. After all, much of NIDA’s portfolio is about describing how much various drugs make one “feel good”. Why doesn’t that encourage drug use? Why is it different to explore higher levels of “feel good”?

NIDA isn’t necessary for funding, of course. One can see where this research might be of interest to the NIMH from a basic neuroscience of behavior perspective. Indeed it wouldn’t be a stretch to see this as linking into some therapeutic avenues. Nevertheless this whole thing illustrates a fairly concrete flaw in the system. The study was excellent work with some obvious avenues of interest to basic neuroscience and indeed the public at large. Yet funding of additional work is going to be hard to come by, NIH-wise, because of the rather rigid NIDA position. Seems a shame.

January 8, 2008 at 5:05 pm

Abel and Sol both touch on a 2006 study. . .”

Don’t think I’ve ever been fortunate to be in the same sentence with Sol with either my real name or my pseudonym – thanks.

I had never seen Volkow’s press release following publication of the Griffiths paper until now – quite surprising that NIDA wouldn’t want to take credit for any well-done, high-impact research, regardless of the prevailing politics of drugs that have the potential for abuse (which you know is low for hallucinogens relative to opioids or even alcohol or nicotine).

Very enlightening. Thanks for the expansive follow-up. I’ve learned a lot.

LikeLike

January 9, 2008 at 6:10 am

Th scuttlebutt was certainly interesting on this whole thing. Rumor of a quashed grant app! Fun stuff…

LikeLike

January 9, 2008 at 6:42 am

“quite surprising that NIDA wouldn’t want to take credit for any well-done, high-impact research, regardless of the prevailing politics of drugs that have the potential for abuse”

You’re kidding, right? If not, then where you been for the last seven years?

LikeLike

January 9, 2008 at 10:59 am

More than 7 years. Alan Leshner started as director in 1994 and he was pretty hardline as well. Schuster was head from 1986-1992 (a bit on NIDA history here). While I wasn’t really NIDA-aware then, Schuster’s subsequent perspectives suggest a less hard line view. As in he might have been interested in more than just the drugs-are-bad thing. Given the realities of the “just say no” meme, the len bias thing, the treatment of “the crack epidemic”, etc in the late eighties, well, I would imagine his course was pretty much set for him no matter his personal beliefs.

LikeLike

January 9, 2008 at 11:37 am

I’m sure you’re correct. I wasn’t speaking from any specific knowledge about NIDA, but rather from the laughableness of the idea that any executive agency under the current administration would do anything “regardless of the prevailing politics”.

LikeLike

January 9, 2008 at 1:11 pm

shhhh. you’re going to draw the cranks!

LikeLike

January 9, 2008 at 2:55 pm

I didn’t use any magic crank-magnet words.

LikeLike

July 6, 2008 at 1:19 am

There is a new psilocybin study underway at Johns Hopkins University that is recruiting volunteers with a past or present diagnosis of cancer.

It looks like the study will only accept a limited number of volunteers so contact the researchers at (410) 550 5990 or visit:

http://www.bpru.org/cancer/insight/

Thanks,

NQ

LikeLike

March 2, 2009 at 10:52 am

NIDA-aware= drugs-are-bad= the “just say no” meme,= the len bias thing= shhhh. you’re going to draw the cranks!

Who Are the cranks???

I’m starting to get the equation… NIDA Aware is code for enforcing the puritan ethos… ultimately banning anything that could lead to sociaL EMPATHY…

you cannot have people to empathetic if you want them to compete in the marketplace.

LikeLike

March 2, 2009 at 12:26 pm

NIDA Aware is not code for enforcing the puritan ethos. It refers to the fact that I was not at that time interested in drug abuse science nor all that knowledgeable about how it was funded or conducted.

“the cranks” are a certain variety of pro-recreation-drug person that occasionally comes by the blog (more common now, thanks to the higher profile and traffic level we enjoy on Sb) and wants to deny the underlying science related to drug abuse topics. I was jesting here because for the most part I think the cranks do a better job of illustrating a certain PR problem that scientists have than I could ever do. In short, I welcome them as long as they don’t get too trollish or repetitive.

LikeLike

March 3, 2009 at 2:48 pm

“Cranks”– these seem to be stigmatized people– people who enjoy recreational drug use– is that so bad? Some see drug use as perfectly natural– as natural as falling in love (R.Siegel,1989) In fact if recreational drug users are enjoying their drug experience then they must be doing it in a controlled manner. Perhaps we could learn something about dose control from them instead of stigmatizing them and they could learn something from science if the communication is left open– such as you are doing right now! I hope I’m not being too “trollish”.

LikeLike

March 4, 2009 at 10:22 am

“Cranks”– these seem to be stigmatized people– people who enjoy recreational drug use– is that so bad?

You are misreading what I said. Cranks are a certain subset of those that argue in favor of recreational drugs. The subset that express some fairly reliable anti-science positions. In fact I should probably just call them denialists because cranks are an even more selective group. the denialism boys have some good primers

http://scienceblogs.com/denialism/2007/05/crank_howto.php

http://scienceblogs.com/denialism/about.php

I happen to most get interested by the science denialist part of their phenotype.

LikeLike

March 5, 2009 at 10:48 am

I have no idea what you are writing about… although it seems to be an exercise in stereotyping and stigmatization… all with an elitist and pompous edge to it… well, I tried.

Perhaps we could learn something about dose control from them instead of stigmatizing them and they could learn something from science if the communication is left open–

LikeLike

January 7, 2011 at 8:42 am

IF GOD IS IN THE BRAIN ONLY, THEN RELATIVITY THEORY DOES NOT

MAKE SENSE

Today’s scientists are like religious gurus of earlier times. Whatever they say are accepted as divine truths by lay public as well as the philosophers. When mystics have said that time is unreal, nobody has paid any heed to them. Rather there were some violent reactions against it from eminent philosophers. Richard M. Gale has said that if time is unreal, then 1) there are no temporal facts, 2) nothing is past, present or future and 3) nothing is earlier or later than anything else (Book: The philosophy of time, 1962). Bertrand Russell has also said something similar to that. But he went so far as to say that science, prudence, hope effort, morality-everything becomes meaningless if we accept the view that time is unreal (Mysticism, Book: religion and science, 1961).

But when scientists have shown that at the speed of light time becomes unreal, these same philosophers have simply kept mum. Here also they could have raised their voice of protest. They could have said something like this: “What is your purpose here? Are you trying to popularize mystical world-view amongst us? If not, then why are you wasting your valuable time, money, and energy by explaining to us as to how time can become unreal? Are you mad?” Had they reacted like this, then that would have been consistent with their earlier outbursts. But they had not. This clearly indicates that a blind faith in science is working here. If mystics were mistaken in saying that time is unreal, then why is the same mistake being repeated by the scientists? Why are they now saying that there is no real division of time as past, present and future in the actual world? If there is no such division of time, then is time real, or, unreal? When his lifelong friend Michele Besso died, Einstein wrote in a letter to his widow that “the distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.” Another scientist Paul Davies has also written in one of his books that time does not pass and that there is no such thing as past, present and future (Other Worlds, 1980). Is this very recent statement made by a scientist that “time does not pass” anything different from the much earlier statement made by the mystics that “time is unreal”?

Now some scientists are trying to establish that mystics did not get their sense of spacelessness, timelessness through their meeting with a real divine being. Rather they got this sense from their own brain. But these scientists have forgotten one thing. They have forgotten that scientists are only concerned with the actual world, not with what some fools and idiots might have uttered while they were in deep trance. So if they at all explain as to how something can be timeless, then they will do so not because the parietal lobe of these mystics’ brain was almost completely shut down when they received their sense of timelessness, but because, and only because, there was, or, there was and still is, a timeless state in this universe.

God is said to be spaceless, timeless. If someone now says that God does not exist, then the sentence “God is said to be spaceless, timeless” (S) can have three different meanings. S can mean:

a) Nothing was/is spaceless, timeless in this universe (A),

b) Not God, but someone else has been said to be spaceless, timeless here (B),

c) Not God, but something else has been said to be spaceless, timeless here (C).

It can be shown that if it is true that God does not exist, and if S is also true, then S can only mean C, but neither A nor B. If S means A, then the two words “spaceless” and “timeless” become two meaningless words, because by these two words we cannot indicate anyone or anything, simply because in this universe never there was, is, and will be, anyone or anything that could be properly called spaceless, timeless. Now the very big question is: how can some scientists find meaning and significance in a word like “timeless” that has got no meaning and significance in the real world? If nothing was timeless in the past, then time was not unreal in the past. If nothing is timeless at present, then time is not unreal at present. If nothing will be timeless in future, then time will not be unreal in future. If in this universe time was never unreal, if it is not now, and if it will never be, then why was it necessary for them to show as to how time could be unreal? If nothing was/is/will be timeless, then it can in no way be the business, concern, or headache of the scientists to show how anything can be timeless. If no one in this universe is immortal, then it can in no way be the business, concern, or headache of the scientists to show how anyone can be immortal. Simply, these are none of their business. So, what compelling reason was there behind their action here? If we cannot find any such compelling reason here, then we will be forced to conclude that scientists are involved in some useless activities here that have got no correspondence whatsoever with the actual world, and thus we lose complete faith in science. Therefore we cannot accept A as the proper meaning of S, as this will reduce some activities of the scientists to simply useless activities.

Now can we accept B as the proper meaning of S? No, we cannot. Because there is no real difference in meaning between this sentence and S. Here one supernatural being has been merely replaced by another supernatural being. So, if S is true, then it can only mean that not God, but something else has been said to be spaceless, timeless. Now, what is this “something else” (SE)? Is it still in the universe? Or, was it in the past? Here there are two possibilities:

a) In the past there was something in this universe that was spaceless, timeless,

b) That spaceless, timeless thing (STT) is still there.

We know that the second possibility will not be acceptable to atheists and scientists. So we will proceed with the first one. If STT was in the past, then was it in the very recent past? Or, was it in the universe billions and billions of years ago? Was only a tiny portion of the universe in spaceless, timeless condition? Or, was the whole universe in that condition? Modern science tells us that before the big bang that took place 13.7 billion years ago there was neither space, nor time. Space and time came into being along with the big bang only. So we can say that before the big bang this universe was in a spaceless, timeless state. So it may be that this is the STT. Is this STT then that SE of which mystics spoke when they said that God is spaceless, timeless? But this STT cannot be SE for several reasons. Because it was there 13.7 billion years ago. And man has appeared on earth only 2 to 3 million years ago. And mystical literatures are at the most 2500 years old, if not even less than that. So, if we now say that STT is SE, then we will have to admit that mystics have somehow come to know that almost 13.7 billion years ago this universe was in a spaceless, timeless condition, which is unbelievable. Therefore we cannot accept that STT is SE. The only other alternative is that this SE was not in the external world at all. As scientist Victor J. Stenger has said, so we can also say that this SE was in mystics’ head only. But if SE was in mystics’ head only, then why was it not kept buried there? Why was it necessary for the scientists to drag it in the outside world, and then to show as to how a state of timelessness could be reached? If mystics’ sense of timelessness was in no way connected with the external world, then how will one justify scientists’ action here? Did these scientists think that the inside portion of the mystics’ head is the real world? And so, when these mystics got their sense of timelessness from their head only and not from any other external source, then that should only be construed as a state of timelessness in the real world? And therefore, as scientists they were obliged to show as to how that state could be reached?

We can conclude this essay with the following observations: If mystical experience is a hallucination, then SE cannot be in the external world. Because in that case mystics’ sense of spacelessness, timelessness will have a correspondence with some external fact, and therefore it will no longer remain a hallucination. But if SE is in mystics’ head only, then that will also create a severe problem. Because in that case we are admitting that the inside portion of mystics’ head is the real world for the scientists. That is why when mystics get their sense of timelessness from their brain, that sense is treated by these scientists as a state of timelessness in the real world, and accordingly they proceed to explain as to how that state can be reached. And we end up this essay with this absurd statement: If mystical experience is a hallucination, then the inside portion of mystics’ head is the real world for the scientists.

LikeLike

September 18, 2011 at 12:09 am

” But this STT cannot be SE for several reasons. Because it was there 13.7 billion years ago. And man has appeared on earth only 2 to 3 million years ago. And mystical literatures are at the most 2500 years old, if not even less than that. So, if we now say that STT is SE, then we will have to admit that mystics have somehow come to know that almost 13.7 billion years ago this universe was in a spaceless, timeless condition, which is unbelievable. ”

Mystics wouldn’t have been able to record these literatures and feelings of the spaceless, timeless “visions” or thoughts they would’ve had. It is even said that the ancient Greeks have had ruins found such as statues, or other relics that have recorded the use of ethneogenic substances such as psilocybin mushrooms. Not that I am saying that all people who have had the idea of time being unreal, or that there is a certain entity outside of this universe that could be the spaceless, timeless thing or not. But in my brief research that I have been conducting for the past few days shows that people who have used these ethneogenic substances have had ideas of what is being stated above^^

Another opinion/idea that I have is that these substances do not naturally grow everywhere on the earth, and the human species has migrated for millions of years to get to where these substances could’ve been. On top of that statement, mankind wasn’t able to record these experiences until Neanderthals could make cave drawings, or until the Sumerians had come up with the first way of communication that could be recorded. In my opinion this spaceless, timeless condition, can be believable.

LikeLike